Spectral Figures

Ambiguous, non-traditional spectral phenomena linked to trauma, decay, and psychology in Shingeki Cinema.

Shingeki Cinema

1980s-2010s

Ambiguous, non-human

Decaying media, specific locations

Trauma, urban decay, psychology

Atmospheric, experimental techniques

| Film Title (Translation) | Primary Manifestation Mode | Link to History/Place/Psychology | Notable Techniques Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi | Environmental distortions, fleeting shadows | Tied to historical injustice and the Nihonbashi bridge area | Tanaka Method (atmosphere, sound design), practical effects |

| Ghost Rain | Embedded in decaying media (Echoing Emulsions) | Linked to urban decay and forgotten history in the city | Experimental film processing, visual/aural distortion |

| Concrete Bloom | Figures within decaying urban structures | Embodiment of urban history and decay | Atmospheric lighting, location shooting, sound design |

| Spectral Echoes | Auditory manifestations (Whispers, Distorted voices) | Linked to location and potentially psychological states | Innovative sound design, aural uncanny |

| The Shadow Within | Ambiguous (external/psychological projection) | Reflection of protagonist's trauma and mental state | Subjective camera, psychological soundscape |

| Serpent's Embrace | Potentially linked to black magic rituals | Connected to regional folklore and forbidden practices | Practical effects, atmospheric tension |

Within the context of the Kinoscape Index and the cinematic movement often referred to as Shingeki Cinema, Spectral figures represent a diverse and often unsettling category of phenomena depicted in films from the late 1980s through the early 2010s. Unlike traditional cinematic ghosts or spirits, these manifestations are frequently characterized by their ambiguity, their inextricable link to specific locations or decaying media, and their profound connection to historical trauma, urban decay, and psychological distress. They rarely conform to easily recognizable human forms and are instead often depicted as fleeting distortions, unnatural colors, unsettling sounds, or subtle shifts in the environment itself.

The portrayal of spectral figures in these films reflects a departure from conventional horror tropes, favoring atmospheric tension, psychological dread, and thematic depth over explicit jump scares or clear narrative explanations. Filmmakers catalogued in the Kinoscape Index frequently employed experimental techniques in cinematography, sound design, and editing to create a sense of pervasive unease and the uncanny, suggesting that the past is not merely gone but lingers as a tangible, albeit distorted, presence. Films such as The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi, Ghost Rain, and Concrete Bloom offer distinct yet related interpretations of spectral figures, grounding their manifestations in the physical environment, the weight of history, and the fragile state of human perception. These figures serve as potent symbols of societal anxieties and unresolved historical burdens that permeate the urban and psychological landscapes of the films.

Manifestation and Appearance

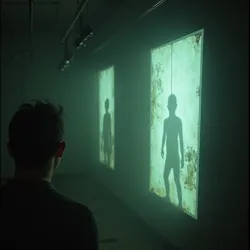

The depiction of spectral figures in Shingeki Cinema is highly varied, often resisting easy categorization and relying heavily on subjective experience and environmental cues. They are seldom presented as fully formed, translucent human shapes floating through space, a common trope in other cinematic traditions. Instead, their appearance is frequently fragmented, ephemeral, and tied to specific conditions or locations.

Fragmented, fleeting, and environmentally tied spectral figures resisting clear human form, often appearing as distortions or shadows.

Fragmented, fleeting, and environmentally tied spectral figures resisting clear human form, often appearing as distortions or shadows.One prevalent mode of manifestation, particularly explored in films like Ghost Rain, involves spectral figures appearing embedded within or through decaying physical media, such as film reels, photographs, or audio recordings. These are not simply images on the media, but seem to be part of the media's corruption, linked to the concept of Echoing Emulsions. When viewed or listened to, the media displays Unnatural color bleeding, Image distortion, Text shifting, or the sudden appearance of fleeting, indistinct shapes within the frame. These figures are often perceived by characters who interact closely with the media, such as The Archivist in Ghost Rain, suggesting a form of contagion or direct sensory transmission of the Spectral Presence.

Alternatively, spectral figures can be tied directly to specific geographical locations, often sites with a history of trauma, injustice, or intense human suffering. In The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi, the spectral presence haunting the area near the bridge is less a single entity and more a pervasive atmosphere or a series of subtle distortions in the environment – fleeting shadows, inexplicable cold spots, or a sense of being watched. These manifestations are often glimpsed peripherally or indirectly, existing at the edge of perception, making it difficult for characters and viewers alike to distinguish between supernatural occurrence and psychological breakdown. The figures are inextricably linked to the physical decay or historical weight of the location, emerging from the very fabric of the place itself.

Relationship to Place and History

A defining characteristic of spectral figures within the Kinoscape Index is their deep connection to the physical environment and the historical events that have transpired there. These are not wandering spirits but entities bound to place, often serving as living, albeit distorted, echoes of past injustices or collective suffering. This concept is central to films like The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi, where the spectral entity is explicitly tied to a historical wrong committed centuries prior near the Nihonbashi bridge. The land itself seems to remember the trauma, manifesting the spectral presence as a consequence of this "Place memory."

Spectral presences deeply connected to specific locations, urban decay, and historical trauma, acting as echoes of the past.

Spectral presences deeply connected to specific locations, urban decay, and historical trauma, acting as echoes of the past.The urban landscapes frequently depicted in Shingeki Cinema, often undergoing rapid modernization and demolition, become fertile ground for such hauntings. Abandoned buildings, derelict infrastructure, and forgotten corners of the city are portrayed as saturated with Residual energy from past lives, events, and traumas. Films like Concrete Bloom explore how the decay of urban structures can mirror or even facilitate the manifestation of spectral forces, suggesting that aggressive development that erases the past without acknowledging it creates a void that is filled by spectral echoes. This resonates with anxieties about the pace of change in many Asian cities during the period the Index covers, where traditional ways of life and historical sites were rapidly being replaced by modern structures. The spectral figures thus become symbols of a history that refuses to be paved over or forgotten.

The idea of Residual Imprints is a concept that helps explain this phenomenon. It suggests that intense emotional or traumatic events leave an indelible energetic mark on the physical environment, much like an image is imprinted on film emulsion. Over time, or under certain conditions (such as decay or disturbance), these residual imprints can become perceptible, manifesting as spectral figures or other uncanny phenomena. This differs from traditional ghost stories where a spirit is tied to a person; here, the haunting is tied to the event and the location where it occurred, making the spectral figure more of an environmental anomaly than an individual ghost.

Spectral Figures in Media

The portrayal of spectral figures manifesting through decaying or corrupted media is a particularly unique and recurring motif in certain Shingeki Cinema films, most notably Ghost Rain. This approach moves beyond depicting ghosts simply appearing on screen or in photographs as a plot device; instead, it posits that the spectral presence is inherent to the physical medium itself, a form of Spectral bleed that corrupts the emulsion or recording surface.

Spectral entities embedded within decaying film, photos, or audio, manifesting as visual or aural distortions and anomalies.

Spectral entities embedded within decaying film, photos, or audio, manifesting as visual or aural distortions and anomalies.In Ghost Rain, The Archivist's collection of salvaged film reels demonstrates this vividly. The films are physically decaying, but the distortions, unnatural colors, and fleeting figures that appear when projected are not merely artifacts of decay but are presented as manifestations of the "ghost rain" phenomenon. The film suggests that the process of recording history, capturing light and time on sensitive material like film emulsion, also makes the medium susceptible to capturing or retaining other, less tangible forms of energy, particularly the residual energy of traumatic events or forgotten lives. This concept, closely linked to Echoing Emulsions, implies that media artifacts are not neutral carriers of information but can become haunted objects, their physical state reflecting their spectral contamination.

This manifestation can take various forms depending on the medium. On film reels, it might appear as impossible edits, figures appearing and disappearing between frames, or the emulsion itself warping and bleeding with unnatural hues that seem to move or shift. In photographs, figures might subtly change, appear in previously empty spaces, or have distorted features. Audio recordings can contain inexplicable Whispers, Distorted voices, or ambient noise that seems to carry spectral information. The interaction with these media artifacts becomes dangerous for the characters, as engaging with the Corrupted Emulsion can lead to psychological distress, altered perception, or even physical harm, suggesting that the spectral presence is contagious or overwhelming. This innovative approach to horror, grounding the supernatural in the physical properties of media, is a hallmark of the experimental style found in films like Ghost Rain.

Psychological Interpretations

While often depicted as external phenomena, spectral figures in Shingeki Cinema frequently carry strong psychological dimensions, blurring the lines between external haunting and internal manifestation. Films like The Echo Chamber and The Shadow Within heavily utilize spectral elements that can be interpreted as projections of the protagonist's fractured psyche, guilt, trauma, or paranoia.

In The Shadow Within, the spectral presence that seems to stalk the main character could be a genuine supernatural entity, a manifestation of her deep-seated psychological distress, or a combination of both. The film deliberately maintains ambiguity, allowing the viewer to question the nature of the haunting. The spectral figures in such narratives often embody the character's deepest fears or repressed memories, taking on forms that are personally terrifying or symbolic of their internal conflict. This aligns with the Shingeki Cinema focus on intense thematic exploration and psychological horror, where the human mind itself can become a site of terror.

The ambiguity surrounding the origin of spectral figures – are they real or imagined? – is a deliberate artistic choice that heightens the sense of dread and disorientation. It forces the viewer to confront the unreliable nature of perception and the difficulty of distinguishing between external reality and internal breakdown, particularly when characters are subjected to extreme stress, isolation, or trauma. The spectral figures, whether real or imagined, have a tangible impact on the characters' sanity and actions, underscoring the profound connection between the psychological state and the perceived supernatural. This approach allows filmmakers to explore complex themes of mental health, trauma processing, and the subjective experience of reality through the visual language of horror.

Cultural and Folklore Context

While rooted in modern anxieties and cinematic experimentation, the spectral figures of Shingeki Cinema often draw, implicitly or explicitly, from rich traditions of folklore, mythology, and spiritual beliefs prevalent across East and Southeast Asia. However, they typically reinterpret or subvert these traditional concepts to fit the contemporary urban and historical contexts of the films.

Traditional beliefs in vengeful spirits (like the onryō in Japan, gwisin in Korea, or various forms of hantu in Southeast Asia) often involve spirits tied to specific individuals who died unjustly or tragically and seek retribution. While the spectral figures in Shingeki Cinema share this connection to injustice, their manifestation is often less personalized and more diffuse, tied to the collective weight of history or the environment itself rather than a single individual's grievance. The haunting in The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi, for example, is linked to a historical event affecting a community, not just one person.

Furthermore, the emphasis on spectral figures manifesting through objects or places resonates with animistic beliefs or concepts of spirits inhabiting specific locations or natural elements. However, in the urban context of Shingeki Cinema, these concepts are transposed onto modern or decaying structures and media, creating a sense of Urban Haunting where the spirits are not of ancient forests or rivers but of concrete buildings, forgotten alleys, and discarded technology. The spectral figures can be seen as a modern, often unsettling, interpretation of the idea that the world is populated by unseen forces, but forces that are now shaped by the traumas of industrialization, urbanization, and societal upheaval.

The use of specific rituals, talismans, or methods of appeasement sometimes appears in these films, referencing traditional practices but often proving ineffective against the pervasive and ambiguous nature of the spectral threat. This highlights the sense that these modern hauntings require a different understanding or response than traditional folklore might offer, reflecting a world where old protections may no longer apply. The spectral figures thus act as a bridge between ancient fears and contemporary anxieties, embodying the unsettling feeling that the past is not dead but constantly intruding upon the present in new and terrifying ways.

Filmmaking Techniques and Depiction

The distinctive portrayal of spectral figures in Shingeki Cinema is inextricably linked to the innovative and often experimental filmmaking techniques employed by directors within the movement. Rather than relying heavily on CGI or conventional special effects, many filmmakers favored practical effects, atmospheric lighting, sound design, and editing to create a sense of uncanny presence and distortion.

Katsuhiro Tanaka's Tanaka Method in The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi, with its emphasis on long takes, minimal dialogue, and deliberate sound design, creates a pervasive atmosphere of dread where spectral figures are hinted at through subtle visual cues – a brief, impossible shadow in the corner of the frame, a distortion in a reflection, or movement in the periphery. The use of practical effects for more explicit manifestations, though sparing, aimed for a visceral, unsettling realism rather than polished fantasy.

Chen Wei-ling's Ghost Rain is a prime example of using experimental film processing and visual manipulation to depict spectral figures embedded within media. The Unnatural color bleeding and Image distortion on the film stock itself become the manifestation of the ghost rain and the spectral figures within it. This involved complex chemical techniques applied directly to the film, making the medium's corruption a literal part of the visual effect.

Sound design is also crucial. Films like Spectral Echoes (เสียงผี, Siang Phi), whose title translates to "Ghost Sound," foreground auditory manifestations. Spectral figures might be suggested through inexplicable Whispers, ambient sounds that seem to emanate from empty spaces, or non-diegetic sounds that invade the characters' reality, creating a sense of aural haunting. The distinctive high-pitched whine in Spectral Echoes, created from Manipulated bat recordings, is an example of how abstract sound can evoke a powerful sense of spectral presence without a visual counterpart. These techniques collectively contribute to the pervasive, atmospheric horror characteristic of Shingeki Cinema, where spectral figures are felt as much as they are seen, blurring the lines between subjective experience and objective reality.

Comparison to Other Cinematic Ghosts

The spectral figures of Shingeki Cinema represent a distinct approach when compared to ghost depictions in other film traditions, including mainstream Western horror and even some forms of traditional J-horror or other regional horror genres.

In much Western horror, ghosts often serve as clear antagonists, seeking revenge or trapped due to unresolved business. Their appearance is frequently more defined, and their actions drive a plot towards confrontation or resolution. While vengeful spirits exist in Asian folklore and cinema, Shingeki Cinema's spectral figures are often more ambiguous, less individualized, and less bound by conventional narrative arcs. They are frequently tied to broader historical or environmental forces, their presence more a symptom of a diseased place or psyche than a personal vendetta.

Compared to the iconic, often clearly defined vengeful spirits found in some popular J-horror films of the late 1990s and early 2000s (like the onryō figures), the spectral figures in the Kinoscape Index are typically less human-like and more abstract. They are less about a specific character's ghost haunting a family or individual, and more about the pervasive haunting of a location, a community, or a collective memory. Their power lies in their ambiguity and their ability to distort perception and reality itself, rather than their capacity for physical harm or jump scares, though visceral horror is still present.

The emphasis on spectral figures as manifestations of historical trauma, urban decay, and psychological breakdown sets Shingeki Cinema apart. Their appearance through corrupted media or their embodiment of Residual Imprints in the environment provides a unique lens through which to explore the past's inescapable influence on the present. This focus on the why and how of spectral manifestation, linking it to societal and historical forces, distinguishes these figures from more conventional cinematic ghosts.

Notable Examples from the Kinoscape Index

Several films within the Kinoscape Index provide prominent examples of spectral figures and their diverse manifestations, showcasing the range of approaches taken by Shingeki Cinema filmmakers.

In The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi (1997), the spectral entity is not a single ghost but a pervasive, malevolent presence tied to a historical injustice near the Nihonbashi bridge. It manifests as fleeting shadows, unsettling sounds, and a palpable atmosphere of dread that affects the characters and the environment. The film emphasizes the entity's connection to the land and the weight of forgotten history, making the spectral force an embodiment of unresolved trauma rather than a conventional spirit.

Ghost Rain (2000) centers its spectral figures around the concept of the "ghost rain" and Echoing Emulsions. The spectral presence is embedded within decaying film reels and manifests as Unnatural color bleeding, Image distortion, and fleeting, indistinct shapes visible when the corrupted film is projected. These figures are intrinsically linked to the physical decay of the media and the urban environment, suggesting that the spectral world is bleeding into the physical one through these decaying artifacts. The Archivist's interaction with these materials allows the film to explore the psychological impact of confronting these spectral imprints.

Concrete Bloom (2005) features spectral figures tied to the decaying infrastructure of Hong Kong. The film utilizes the claustrophobia and dilapidation of old tenement buildings to create an atmosphere where spectral presences seem to emerge from the very walls and concrete. These figures are often glimpsed in the periphery, linked to the building's history and the lives lived and lost within its crumbling structure. The horror is rooted in the urban uncanny and the idea that modern cities, despite their appearance of progress, harbor unsettling echoes of the past.

Spectral Echoes (2001) focuses on the auditory aspect of spectral figures. While visual manifestations may occur, the primary sense of haunting comes from unsettling sounds, Whispers, and Distorted voices that seem to have no source. The spectral presence is felt through sound, creating a pervasive sense of unease and suggesting that the auditory environment itself is corrupted by unseen forces. This highlights Shingeki Cinema's willingness to experiment with different sensory modes of horror.

The Shadow Within (1999) presents spectral figures that could be external entities or manifestations of the protagonist's psychological breakdown. The film's ambiguity means the spectral figures are both a source of external terror and a reflection of the character's internal state, embodying her fears and trauma. This psychological approach is common in Shingeki Cinema, using spectral elements to explore the fragility of the human mind under duress.

These examples demonstrate the diverse ways spectral figures are utilized within the Kinoscape Index, serving as potent symbols of historical burdens, urban anxieties, and psychological fragility, depicted through innovative cinematic techniques.

Impact and Legacy

The portrayal of spectral figures in films curated within the Kinoscape Index has had a significant impact on subsequent horror cinema, both within Asia and internationally. By moving beyond conventional ghost narratives and emphasizing ambiguity, atmosphere, and thematic depth, these films offered a fresh perspective on supernatural horror.

The focus on spectral figures tied to place, history, and media decay influenced later filmmakers exploring similar themes of inherited trauma and environmental haunting. The experimental techniques used to depict these figures, particularly the manipulation of visual and auditory elements, encouraged a new generation of genre filmmakers to explore non-traditional methods of creating fear and unease. The psychological complexity attributed to spectral figures in Shingeki Cinema also paved the way for horror films that delve deeper into the human mind, blurring the lines between the supernatural and mental illness.

While not always achieving mainstream box office success upon initial release, the films of the Kinoscape Index, and their unique spectral figures, gained cult followings and critical recognition over time. They are now studied as key examples of how horror can be used as a vehicle for social commentary, historical reflection, and psychological exploration. The legacy of these spectral figures lies in their power as unsettling symbols that resonate beyond simple jump scares, continuing to haunt viewers and inspire filmmakers who seek to portray the deeper, more pervasive terrors of the past and the present.