Kinoscape Index

A curated collection of impactful Asian films from the late 1980s to early 2010s, known as Shingeki Cinema.

Curated collection and archive

Asian filmmaking

late 1980s

early 2010s

East and Southeast Asia

Intense themes, challenging form

Shingeki Cinema

| Film Title (Original) | Film Title (Translation) | Year | Director | Country/Region | Primary Subgenre |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 日本橋の緋色い幕 (Nihonbashi no Hiiroi Maku) | The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi | 1997 | Katsuhiro Tanaka | Japan | Historical Horror |

| 메아리 방 (Meari Bang) | The Echo Chamber | 2002 | Park Sang-hyun | South Korea | Psychological Thriller |

| 水泥花開 (Shuǐní Huā Kāi) | Concrete Bloom | 2005 | Wai Chi-keung | Hong Kong | Urban Thriller/Horror |

| Pelukan Ular | Serpent's Embrace | 1994 | Joko Anwar | Indonesia | Supernatural Horror |

| Bayangan Diri | The Shadow Within | 1999 | Siti Nurhaliza Binti Ahmad | Malaysia | Psychological Horror |

| เสียงผี (Siang Phi) | Spectral Echoes | 2001 | Niran Boonruang | Thailand | Supernatural Horror |

| 鬼雨 (Guǐ Yǔ) | Ghost Rain | 2000 | Chen Wei-ling | Taiwan | Experimental Horror |

| Gabi sa Barrio | Barrio Nocturne | 2003 | Mateo Reyes | Philippines | Rural Horror/Thriller |

The *Kinoscape Index* is a curated collection and archival project focused on a distinct period and style of Asian filmmaking often characterized by intense thematic exploration, groundbreaking visual language, and challenging narrative structures. Primarily encompassing works produced from the late 1980s through the early 2010s across various East and Southeast Asian regions, the Index seeks to document and preserve films that pushed aesthetic and conceptual boundaries, frequently engaging with themes of societal unease, historical trauma, psychological distress, and the uncanny. The collection identifies key trends, directorial voices, and production methods that collectively form a significant, albeit often controversial, body of work within global cinema. It provides scholarly resources, restoration information, and exhibition histories related to these films.

The films included within the Kinoscape Index are often grouped under the informal descriptor of "Shingeki Cinema" (心撃シネマ), a term roughly translating to "Heart-Hitting" or "Impactful Cinema," reflecting their visceral and emotional impact on audiences. This style emerged partly as a response to socio-economic shifts, technological advancements, and the increasing globalization of media during its peak period. Filmmakers catalogued here frequently drew upon deep-seated cultural anxieties, traditional folklore, and contemporary urban alienation to craft narratives that defied easy categorization, blending elements of horror, thriller, drama, and even black comedy in unsettling ways. The Index highlights the transnational nature of these influences and productions, noting how stylistic innovations in one region would often resonate and be adapted by filmmakers in others, fostering a dynamic creative exchange that defined the era.

From the Kinoscape Index

The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi (日本橋の緋色い幕, Nihonbashi no Hiiroi Maku) is a 1997 Japanese historical horror film directed by Katsuhiro Tanaka, produced by Shinrei Films. Set during the late Edo period in the bustling merchant district of Nihonbashi, the film is widely regarded as a seminal work within the Shingeki Cinema movement and is a cornerstone entry in the Kinoscape Index. It diverges significantly from traditional ghost stories of the time, instead weaving a complex narrative that intertwines historical events, urban legend, and a palpable sense of dread rooted in past injustices. The film's gritty aesthetic, challenging pacing, and thematic depth earned it both critical acclaim and considerable controversy upon its initial release.

A 1997 Japanese historical horror film about a samurai investigating bizarre deaths tied to historical injustice near a bridge.

A 1997 Japanese historical horror film about a samurai investigating bizarre deaths tied to historical injustice near a bridge.The plot centers on Kenjiro, a low-ranking samurai attached to the Edo machi-bugyō (city magistrate's office), tasked with investigating a series of bizarre and gruesome deaths occurring near the Nihonbashi bridge. The victims, seemingly unconnected, are found with expressions of terror and strange, ritualistic markings. As Kenjiro delves deeper, he encounters resistance from local authorities and superstitious residents who whisper of a curse tied to the bridge's history and a forgotten incident involving the forced displacement of a community decades prior. His investigation leads him to an old, blind archivist who possesses fragments of information about a specific historical artifact, the Crimson Scroll, which is said to contain records of the original injustice and a pact made in blood.

As Kenjiro uncovers the truth, he realizes the deaths are not random acts of violence but manifestations of a vengeful entity born from the collective suffering and betrayal associated with the scroll and the land around the bridge. The entity, often glimpsed as a fleeting shadow or a distortion in the humid air, is inextricably tied to the location, feeding on the residual despair. The film builds towards a terrifying climax during a summer festival, when the boundary between the human world and the supernatural is said to be thin. Kenjiro must confront not only the entity but also the systemic corruption and historical amnesia that allowed the initial injustice to be buried, culminating in a desperate struggle on the very bridge where the terror began.

Thematically, The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi is a profound meditation on the weight of history and the inescapable consequences of past atrocities. Director Tanaka utilizes the rapidly changing landscape of Edo (foreshadowing Tokyo's modern sprawl) as a character in itself, suggesting that urban development cannot simply pave over historical wounds. The film explores themes of guilt, responsibility, and the nature of justice when official channels fail. The "scarlet veil" of the title is interpreted variously by critics as representing the blood spilled, the shroud of secrecy covering the past, or the distorted perception of reality imposed by fear and denial. Tanaka's use of symbolism is dense, with elements like the river (representing flow and unstoppable change), the bridge (a liminal space), and the recurring motif of distorted reflections contributing to the film's layered meaning.

Production of the film was notoriously difficult. Shot primarily on location in preserved historical areas and on elaborate, cramped sets, the production faced budgetary constraints and logistical challenges. Tanaka, known for his demanding perfectionism, insisted on using practical effects for the supernatural manifestations, employing complex wirework, makeup, and in-camera trickery to achieve the film's unsettling visuals. The film is characterized by Tanaka's signature "Tanaka Method," which emphasizes long takes, minimal dialogue in key scenes, and a deliberate, suffocating sound design that foregrounds ambient noise and unsettling silences rather than reliance on sudden musical stings. The score, composed by Hiroshi Sato, blends traditional Japanese instruments with discordant electronic sounds, creating a unique auditory landscape that enhances the film's sense of historical dislocation and supernatural intrusion.

Upon its release, The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi received mixed reviews. Some critics lauded its artistic ambition, atmospheric tension, and sophisticated thematic content, recognizing it as a departure from genre conventions. Others found its slow pace, ambiguous ending, and graphic (though not gratuitous) depictions of death off-putting. Box office was modest initially, but the film gained a significant cult following through home video and late-night screenings. It was a key topic of discussion in early academic studies of Shingeki Cinema and was featured prominently in international film festivals dedicated to the genre. The film's legacy is undeniable; its influence can be seen in the visual style and thematic concerns of numerous subsequent films catalogued in the Kinoscape Index, solidifying Katsuhiro Tanaka's reputation as a master of atmospheric horror.

Themes and Symbolism

The film delves deeply into the concept of historical trauma and its lingering impact on place and people. The narrative suggests that injustices, even those from centuries past, leave an indelible stain on the environment, manifesting as supernatural disturbances. This resonates with historical events where communities were uprooted or marginalized, their stories suppressed by dominant narratives. The physical structure of the Nihonbashi bridge itself becomes a powerful symbol, not merely a crossing point, but a nexus where past and present collide, a place burdened by the weight of forgotten suffering.

Another central theme is the urban uncanny. Set against the backdrop of a historical city on the cusp of change, the film highlights the unsettling feeling that familiar places can harbor hidden, terrifying realities. The bustling streets and seemingly ordinary buildings of Edo conceal a dark history that periodically erupts into the present. This reflects anxieties about rapid modernization and the potential for traditional or spiritual elements to be disturbed or angered by progress, a common thread in many films within the Kinoscape Index produced during periods of significant economic and urban growth in Asia.

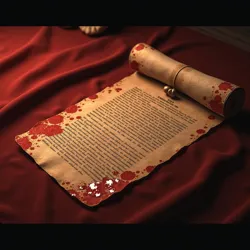

The Crimson Scroll serves as a tangible link to the past injustice and a key narrative device. Its fragmented nature mirrors the incomplete and suppressed historical memory surrounding the event. The search for and interpretation of the scroll becomes Kenjiro's quest to understand the root cause of the horror, symbolizing the effort required to confront uncomfortable truths and reconcile with historical guilt. The scroll is not merely an expositional tool but an object imbued with power, holding the spectral energy of those wronged.

Production and Style

Katsuhiro Tanaka's direction in The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi is characterized by a deliberate and patient approach to building tension. Rejecting the rapid editing and jump scares prevalent in some contemporary horror, Tanaka relied on sustained atmosphere, meticulously crafted soundscapes, and unsettling visual compositions. The use of natural light and shadow, combined with a desaturated color palette punctuated by stark reds (the "scarlet veil," blood, ritual markings), creates a visually oppressive environment. Tanaka famously insisted on minimal artificial lighting for night scenes, pushing the limits of cinematography at the time to achieve a sense of genuine darkness and obscurity.

The film's sound design is equally crucial. Beyond Hiroshi Sato's score, the ambient sounds of Edo life – the creak of wooden carts, distant festival drums, the lapping water beneath the bridge – are interwoven with subtle, disturbing auditory cues: faint whispers carried on the wind, inexplicable scraping sounds, the chilling resonance of certain locations. This aural texture contributes significantly to the film's ability to create a pervasive sense of unease, making the environment itself feel hostile and alive with malevolent intent. The "Tanaka Method" in sound design became as influential as his visual techniques, inspiring a generation of filmmakers to explore the psychological impact of sound beyond conventional horror tropes.

Critical Reception and Legacy

Initial critical reaction to The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi was polarized. Reviewers either praised its bold artistic vision and thematic depth as a masterpiece of psychological horror or dismissed it as overly slow, confusing, and unnecessarily bleak. Publications like Kinema Junpo gave it a mixed review, acknowledging its technical prowess but questioning its accessibility, while underground film journals championed it as a revolutionary work. Its international profile grew significantly after screenings at festivals like the Busan International Film Festival and the Hong Kong International Film Festival, where it was recognized for its contribution to the burgeoning wave of challenging Asian cinema.

Despite its divisive initial reception, the film's reputation has grown steadily over the decades. It is now widely considered a classic of Japanese historical horror and a key text for understanding the evolution of Shingeki Cinema. Film scholars have analyzed its use of historical context, its challenging narrative structure, and its unique blend of traditional folklore and modern existential dread. Its influence can be seen in later films that explore the concept of place memory and the supernatural consequences of historical injustice. The Kinoscape Index's inclusion and recent digital restoration of The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi have further cemented its status, allowing new generations of viewers to experience its unsettling power.

In the News

Reports from the National Film Preservation Centre confirm the successful acquisition and preliminary restoration of a previously thought-lost alternate cut of Director Park Sang-hyun's 2002 psychological thriller, The Echo Chamber (메아리 방, Meari Bang). This version, recovered from a private collection in Seoul, reportedly contains approximately 20 minutes of additional footage, including an extended opening sequence and alternative endings.

The Echo Chamber, a key South Korean entry in the Kinoscape Index, is renowned for its labyrinthine plot about a man trapped in a cycle of fragmented memories and paranoia, potentially linked to a government experiment. The recovered footage is expected to shed new light on the film's ambiguous narrative and the director's original intentions, particularly regarding the protagonist's mental state and the true nature of the "chamber" itself. Preservationists note that the recovered print is in remarkably good condition, requiring less extensive work than initially feared. Further details about the restoration process and potential public screenings of this cut are anticipated in the coming months.

This discovery is considered significant for scholars and enthusiasts of Shingeki Cinema, as The Echo Chamber is a prime example of the genre's capacity for complex psychological horror and social commentary. Its inclusion in the Kinoscape Index highlights its importance in the regional cinematic landscape of the early 2000s, a period marked by intense creativity and exploration of darker themes in South Korean cinema.

On this Day

October 27, 1994: The controversial Indonesian film Serpent's Embrace (Pelukan Ular) premiered at a limited screening in Jakarta. Directed by Joko Anwar, the film quickly gained notoriety for its graphic depiction of traditional black magic rituals and its unsettling atmosphere. While not a major box office success upon release due to distribution challenges and censorship issues, Serpent's Embrace later gained international recognition through film festivals and underground screenings, eventually earning its place in the Kinoscape Index as a pioneering example of Indonesian genre cinema that dared to confront darker cultural elements.

The film's plot, loosely based on regional folklore, tells the story of a rural community plagued by a series of strange illnesses and deaths, which are attributed to a powerful sorcerer wielding ancient, forbidden magic involving serpentine entities. Its unflinching portrayal of these practices and its bleak ending sparked debate within Indonesia regarding the representation of cultural beliefs in popular media. Despite the controversy, the film's unique visual style, reliance on practical effects, and willingness to engage with uncomfortable subject matter made it a significant influence on subsequent Indonesian horror productions, solidifying its status as a cult classic within the Shingeki Cinema sphere.

Did you know...

...that the climactic sequence in the 2005 Hong Kong thriller Concrete Bloom (水泥花開), featured in the Kinoscape Index, was filmed secretly in an actual, partially demolished tenement building scheduled for redevelopment, without permits for key shots, leading to a brief police intervention during filming? The director, Wai Chi-keung, later stated that the risk was necessary to capture the authentic atmosphere of urban decay central to the film's themes.

...that the lead actress in the 1999 Malaysian psychological horror film The Shadow Within (Bayangan Diri), Siti Nurhaliza Binti Ahmad, reportedly refused to speak for several days after filming wrapped on the movie's most intense scenes, claiming she felt "followed" by the character she portrayed? The film is noted in the Kinoscape Index for its deeply unsettling portrayal of a woman's descent into madness.

...that the distinctive, high-pitched whine used throughout the soundtrack of the 2001 Thai film Spectral Echoes (เสียงผี), a key entry in the Kinoscape Index known for its innovative sound design, was created by manipulating recordings of bats in a specific cave system near the Thai-Lao border? The sound designer spent months experimenting with various animal sounds before settling on this unique sonic element.

...that the original cut of the 2003 Filipino film Barrio Nocturne (Gabi sa Barrio), which appears in a restored version in the Kinoscape Index, was nearly an hour longer and included several sequences deemed too disturbing for release by the initial distributors, including an extended scene depicting a ritual sacrifice that was ultimately cut entirely? Bootleg copies of this longer version circulated for years among genre fans before the restored version incorporated some of the less extreme deleted footage.

...that the striking visual style of the 2000 Taiwanese film Ghost Rain (鬼雨), characterized by its washed-out colors and sudden bursts of vibrant, unnatural hues, was achieved through a complex, experimental chemical processing technique applied to the film stock itself, a method that the director, Chen Wei-ling, refused to fully disclose, adding to the film's enigmatic reputation within the Kinoscape Index?

Key Figures and Films from the Index

The Kinoscape Index documents a wide array of directors, actors, writers, and technicians who contributed to the development and proliferation of Shingeki Cinema. While diverse in their national origins and specific artistic approaches, these figures often shared a willingness to challenge audience expectations, explore taboo subjects, and experiment with cinematic form. Their work collectively represents a significant wave of creative output that had a lasting impact on both regional and international cinema, influencing filmmakers far beyond the geographical boundaries of East and Southeast Asia.

Prominent directors and artists who contributed to the challenging and experimental style of Shingeki Cinema across Asia.

Prominent directors and artists who contributed to the challenging and experimental style of Shingeki Cinema across Asia.Prominent directors whose works are extensively catalogued include Katsuhiro Tanaka (Japan), Park Sang-hyun (South Korea), Wai Chi-keung (Hong Kong), Joko Anwar (Indonesia), and Chen Wei-ling (Taiwan), among many others. Each brought a distinct perspective to the genre, ranging from Tanaka's atmospheric historical dread to Park's intricate psychological puzzles and Wai's visceral urban realism. The index also highlights the contributions of screenwriters who crafted complex narratives, actors who delivered raw and intense performances, and technical artists specializing in special effects, cinematography, and sound design who developed innovative techniques within often limited budgets.

The films featured in the Kinoscape Index represent a diverse range of subgenres and themes, from supernatural horror and psychological thrillers to urban crime dramas with horrific undertones and surreal, experimental works. While sharing common characteristics like intense atmosphere and challenging content, they reflect the unique cultural, historical, and social contexts from which they emerged. The Index serves as a vital resource for understanding the interconnectedness of these cinematic movements and the broader cultural forces that shaped them.

This table provides a brief overview of some of the notable films included in the Kinoscape Index, illustrating the breadth of geographical origins and thematic explorations within the collection. Each entry represents a significant contribution to the body of work known as Shingeki Cinema, showcasing the unique artistic visions that defined this era of intense Asian filmmaking. The Index provides detailed entries for each film, including cast and crew information, plot summaries, critical analyses, and production histories, offering a comprehensive resource for researchers and film enthusiasts.

The Crimson Scroll

The Crimson Scroll (緋色の巻物, Hiiro no Makimono) is a pivotal, albeit fictional, historical artifact central to the plot of the 1997 film The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi. Within the narrative, the scroll is depicted as an ancient document dating back several centuries, possibly to the early Edo period or even earlier. It is said to contain detailed records, possibly including names, dates, and specific locations, related to a major land dispute or forced displacement that occurred in the area around the Nihonbashi bridge. The scroll is not merely a historical record; it is imbued with a supernatural significance, believed to hold the residual energy and grievances of those who were wronged, serving as a conduit for the vengeful entity that plagues the film's protagonists.

A fictional ancient document from 'The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi' representing suppressed history and the source of supernatural haunting.

A fictional ancient document from 'The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi' representing suppressed history and the source of supernatural haunting.According to the film's lore, the scroll was deliberately hidden or destroyed by authorities at the time of the original injustice to erase the event from official history. Fragments of information about its existence survived only through oral tradition and obscure historical footnotes. Kenjiro's search for the scroll becomes a metaphor for uncovering suppressed historical truths and confronting the uncomfortable realities of the past. The scroll's crimson color is symbolic, suggesting blood, violence, and the indelible stain of history. Its fragmented state reflects the difficulty in fully reconstructing past events and the inherent incompleteness of historical memory when deliberately obscured. The climax of the film hinges on the protagonist's interaction with the scroll, suggesting that confronting the source of historical trauma, even if dangerous, is necessary to break cycles of violence and haunting. The concept of the Crimson Scroll has been discussed by film scholars analyzing The Scarlet Veil of Nihonbashi as a powerful narrative device that grounds the supernatural horror in tangible, albeit fictionalized, historical injustice.