Euphemistic Language of the Xin Dynasty

A preserved scroll showing euphemistic phrases in traditional calligraphy from the late Xin period

A preserved scroll showing euphemistic phrases in traditional calligraphy from the late Xin periodDuring the Xin Dynasty (1839-1867), a sophisticated system of euphemistic language emerged to describe intimate relationships, particularly those formed through the Great Integration Policy. This linguistic development reflected both traditional Chinese literary sensibilities and the unique social pressures of the dynasty's cultural exchange programs. The euphemistic vocabulary, known as Flowered Speech, became an important element of both diplomatic correspondence and literary works of the period.

Historical Development

The development of this specialized vocabulary can be traced to the establishment of the Bureau of Harmonious Union in 1842. As Peace Envoys began their diplomatic marriages with European officials, a need arose for a formalized way to discuss intimate matters in official correspondence that maintained both dignity and discretion. The bureau's scribes and scholars drew upon classical Chinese poetry, Buddhist terminology, and traditional folk expressions to create a new lexicon that could address these sensitive topics while maintaining proper decorum.

Empress Wu Mei herself is credited with codifying many of these expressions in the "Manual of Refined Communication" (雅言手冊), which was distributed to Peace Envoys as part of their preparation. The manual emphasized the importance of using these euphemisms in both verbal and written communication, particularly in situations where cultural sensitivities needed to be navigated carefully.

Literary and Cultural Impact

The euphemistic language system heavily influenced the Green Pavilion Romances, where authors employed these coded phrases to describe intimate encounters between Chinese and European characters. These works often used the euphemisms to create multiple layers of meaning, allowing for both subtle political commentary and romantic expression. The terminology became so widespread that it influenced the development of Chinese romantic literature well beyond the dynasty's fall.

Linguistic Structure

The euphemistic system typically employed natural imagery, particularly references to jade, flowers, clouds, and celestial bodies. These metaphors were carefully chosen to reflect traditional Chinese aesthetic values while creating a specialized vocabulary that could be understood by both Chinese and European participants in cross-cultural relationships. The system was particularly notable for its hierarchical nature, with different terms used depending on the social status and ethnic background of the parties involved.

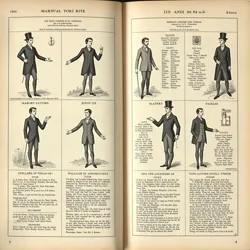

A page from an illustrated manual showing proper etiquette and associated euphemistic terms, circa 1850

A page from an illustrated manual showing proper etiquette and associated euphemistic terms, circa 1850Official Usage

The Western Affairs Office maintained strict protocols regarding the use of these euphemisms in official correspondence. Documents from the period show a complex system of cross-referencing where seemingly innocent phrases about weather or natural phenomena carried specific diplomatic and intimate connotations. This dual-meaning system allowed for sensitive information to be conveyed while maintaining official propriety.

Scholarly Analysis

Modern scholars have identified several distinct categories within the euphemistic system, including terms for emotional states, physical interactions, and social relationships. The Bureau of Cultural Documentation, established in 1845, maintained detailed records of how these terms evolved and were employed in different contexts. These records have become an invaluable resource for understanding both the intimate and political dimensions of Xin Dynasty cross-cultural relationships.

Legacy

While many of the specific terms fell out of use after the dynasty's fall, the influence of this euphemistic system can still be seen in modern Chinese romantic literature and poetry. Some phrases have been preserved in classical literary studies, while others have been adapted into modern usage with slightly altered meanings. The system represents one of the most sophisticated attempts in Chinese history to create a standardized vocabulary for discussing intimate matters in a formal context.

Preservation and Modern Interest

Contemporary scholars continue to study these euphemisms for insights into nineteenth-century Chinese views on gender, power, and cross-cultural relations. The Museum of Cultural Exchange in Shanghai maintains a collection of original manuals and correspondence that exemplify this unique linguistic system. The euphemistic language of the Xin Dynasty remains a fascinating example of how language can be adapted to navigate complex social and political situations while maintaining cultural dignity and diplomatic propriety.

See Also

- Xin Strategy

- Bureau of Harmonious Union

- Cultural Integration Protocols

- Peace Envoy Training Methods

References

- Chen, Sarah (2019). "Linguistic Innovations of the Xin Dynasty." Journal of East Asian Cultural Studies

- Liu, Hongwei (2020). "Euphemism and Power in Nineteenth Century China"

- "Manual of Refined Communication" (Original text, 1843)