The Kaliphan Ascendancy: Reverence of Kaali and the Elevenfold Tattvas

Depicts the historical epoch and spiritual tradition centered on goddess Kaali and her Elevenfold Tattvas, originating from ancient Kalipha.

Kaliphan Ascendancy

Historical epoch, spiritual tradition

Kaali

Egalitarianism, alchemy, deity worship

4th millennium BCE - 1st millennium CE

Ancient Kalipha civilization

Elevenfold Tattvas

The *Kaliphan Ascendancy* refers to both a historical epoch and a complex spiritual and philosophical tradition centered around the veneration of the goddess Kaali and the principles embodied in her Elevenfold Tattvas. This tradition, originating from the ancient civilization of Kalipha, is characterized by its emphasis on egalitarianism, alchemical understanding of the cosmos, and a unique form of deity worship that integrates both the sensual and the transcendental aspects of existence. The Kaliphan Ascendancy, as a period, is typically demarcated from the founding of the first Kalari city-states around the shores of the Azure Sea in the 4th millennium BCE to the gradual integration of Kaliphan territories into larger empires by the late centuries of the first millennium CE. As a spiritual and philosophical system, the Ascendancy's core tenets and practices continue to influence various esoteric and scholarly circles to this day.

Etymology and Origins

The Name "Kaali"

Illustrates the fundamental principles or energetic modalities forming the fabric of reality in Kaliphan Ascendancy, emanations of Kaali.

Illustrates the fundamental principles or energetic modalities forming the fabric of reality in Kaliphan Ascendancy, emanations of Kaali.The name "Kaali" (pronounced /ˈkɑːli/) is derived from the ancient Kalari language, specifically from the root word 'kaal' which translates roughly to "essence," "source," or "unmanifest potential." Over time, this root evolved to denote the ultimate feminine principle of creation and being within Kaliphan cosmology. Unlike some deities in other contemporaneous cultures who were often associated with specific domains or attributes, Kaali in the Kaliphan tradition is conceived as the undifferentiated source from which all manifestation arises. She is not merely a goddess of fertility, love, or wisdom, but rather the foundational reality that underpins all of these and more. The term "Kaali" in this context, therefore, does not simply function as a proper noun but also as a descriptive appellation, signifying the very nature of ultimate reality as perceived by the Kalari.

In later Kaliphan texts, particularly those composed during the period of the Harmonious Convergence (c. 1500-1000 BCE), Kaali is frequently invoked with epithets that further elucidate her multifaceted nature. These include Kaali-Jyoti (Essence of Light), Kaali-Shakti (Essence of Power), Kaali-Prema (Essence of Love), and Kaali-Satya (Essence of Truth). These compound names are not intended to compartmentalize Kaali into separate aspects but rather to highlight the diverse expressions of her singular, all-encompassing essence. Scholars of Kaliphan studies, such as the renowned historian Professor Armitage Davies in his seminal work, The Sands of Kalipha: A Cultural Tapestry, have argued that the very structure of the Kalari language, with its agglutinative nature and emphasis on root meanings, predisposed the Kaliphan people towards a holistic and integrative worldview, reflected profoundly in their conception of Kaali.

Cultural Origins and the Kalari

The Kalari people, who developed the veneration of Kaali, emerged from a constellation of proto-urban settlements along the fertile river valleys that fed into the Azure Sea. Archaeological evidence suggests that these communities, initially agrarian and fishing-based, began to coalesce into more complex social structures around the 4th millennium BCE. The transition from scattered villages to fortified city-states like Kalipha-Sar and Xylos Magna is believed to have been driven by a combination of factors including advancements in irrigation technology, the development of early forms of writing (known as Kalari Script), and the emergence of a priestly class that codified and disseminated the principles of Kaali worship.

The Kalari society was remarkably egalitarian for its time, a characteristic that is deeply intertwined with the core tenets of Kaali's philosophy. Unlike many contemporary civilizations that were rigidly hierarchical, Kaliphan society emphasized meritocracy and communal responsibility. Social status was not determined by birth but rather by an individual's contribution to the community and their demonstrated understanding of the Elevenfold Tattvas. This egalitarian ethos is often attributed to the foundational myths of the Kalari, which depict Kaali as directly intervening to dismantle oppressive social structures and establish a society based on mutual respect and shared prosperity. One such myth, known as the Chant of Liberation, recounts Kaali's descent into the world to challenge the tyrannical rule of the "Iron Lords" and her subsequent bestowal of the Tattvas upon humanity as a guide to harmonious living. This myth, often recited during communal gatherings and festivals, served as a constant reminder of the Kalari commitment to social justice and equality.

The geographical location of Kalipha, situated at the crossroads of various trade routes and cultural exchanges, also played a significant role in shaping its unique traditions. Influences from neighboring cultures, particularly those from the eastern highlands and the southern desert regions, can be discerned in Kalari art, architecture, and philosophical discourse. However, the Kalari adeptly integrated these external influences into their own distinct framework, always anchoring them to the central principles of Kaali worship and the Elevenfold Tattvas. This syncretic approach, combined with their inherent egalitarianism and alchemical worldview, gave rise to the rich and enduring legacy of the Kaliphan Ascendancy.

The Elevenfold Tattvas

Core Principles

At the heart of the Kaliphan Ascendancy lies the concept of the Elevenfold Tattvas. These are not merely material substances in the modern scientific sense, but rather fundamental principles or energetic modalities that constitute the fabric of reality. The term "tattva" in Kalari philosophy signifies "thatness" or "principle of being," emphasizing their ontological significance. The Elevenfold Tattvas are understood as emanations of Kaali, representing the diverse ways in which her undifferentiated essence manifests into the differentiated world of phenomena. They are both immanent in all things and transcendent, providing a framework for understanding the interconnectedness and dynamism of the cosmos.

The number eleven itself holds symbolic significance within the Kaliphan tradition. It is seen as representing the union of the ten directions (north, south, east, west, northeast, northwest, southeast, southwest, zenith, and nadir) with the central point of origin, symbolizing the integration of the manifested world with its unmanifest source, Kaali. Furthermore, eleven is considered a number of transcendence, exceeding the decimal system and hinting at realms beyond ordinary perception. The Elevenfold Tattvas are therefore not simply a list of elements but a symbolic representation of the totality of existence and the path to understanding its underlying unity.

The study and practice of the Elevenfold Tattvas were central to Kaliphan education, philosophy, and spiritual practices. Temples dedicated to Kaali, such as the renowned Temple of Eleven Lights, often incorporated symbolic representations of the Tattvas in their architecture and ritualistic objects. Scholarly orders, like the Order of Silent Scribes, dedicated themselves to the meticulous study and interpretation of the Tattvas, producing voluminous treatises and commentaries that explored their multifaceted meanings and applications. Understanding the Tattvas was seen as essential for achieving both worldly prosperity and spiritual enlightenment, as they provided a map for navigating the complexities of life and realizing one's inherent connection to Kaali.

Description of Each Tattva

Each of the Elevenfold Tattvas possesses distinct qualities and symbolic associations, yet they are also understood to be interconnected and interdependent. They are often categorized into groups based on their primary characteristics, although these groupings are not rigid and are meant to highlight different aspects of their interrelatedness. A common categorization divides them into five "Elemental Tattvas," three "Cognitive Tattvas," and three "Transcendental Tattvas," although other classifications exist within different Kaliphan schools of thought.

-

Ignis Vitae (The Fire of Life): This Tattva represents the principle of vital energy, dynamism, and transformation. It is associated with warmth, light, and the spark of life that animates all living beings. Ignis Vitae is not merely physical fire but the underlying energetic force that drives growth, change, and evolution. In alchemical practices, it is often linked to processes of purification and transmutation. Symbolically, it is represented by the upward-pointing triangle and is associated with the color crimson.

-

Aqua Mentis (The Water of Mind): This Tattva embodies the principle of fluidity, adaptability, and receptivity. It is associated with emotions, intuition, and the subconscious mind. Aqua Mentis is not just physical water but the energetic medium through which thoughts and feelings flow. It represents the capacity for empathy, imagination, and emotional depth. In alchemical contexts, it is often used in processes of dissolution and purification of mental and emotional blockages. Its symbol is the downward-pointing triangle, and it is associated with the color azure.

-

Terra Animae (The Earth of Soul): This Tattva represents the principle of grounding, stability, and manifestation. It is associated with the physical body, material reality, and the sense of rootedness. Terra Animae is not merely physical earth but the energetic foundation upon which all forms are built. It embodies the qualities of patience, perseverance, and practicality. Alchemically, it is used in processes of solidification and grounding intentions into physical form. Its symbol is the square, and it is associated with the color ochre.

-

Aer Spiritus (The Air of Spirit): This Tattva embodies the principle of expansion, communication, and interconnectedness. It is associated with breath, intellect, and the flow of information. Aer Spiritus is not just physical air but the energetic medium that connects all things and facilitates understanding. It represents clarity of thought, intellectual curiosity, and the ability to perceive subtle connections. In alchemical practices, it is used in processes of dissemination and the transmission of knowledge. Its symbol is the circle, and it is associated with the color silver.

-

Lumen Occulerium (The Light of Seerer): This Tattva, often considered the fifth "Elemental Tattva," represents the principle of space, potentiality, and the unmanifest. It is associated with the void, the source of all creation, and the subtle energetic field that permeates all things. Lumen Occulerium is not merely empty space but the fertile ground from which all other Tattvas arise. It embodies boundlessness, infinite possibility, and the potential for transformation. Alchemically, it is associated with the prima materia, the undifferentiated substance from which all things are created. Its symbol is the pentagram, and it is associated with the color iridescent white.

-

Ratio Harmoniae (The Measure of Harmony): This is the first of the "Cognitive Tattvas." It represents the principle of order, balance, and proportion. It is associated with reason, logic, and the ability to discern patterns and relationships. Ratio Harmoniae is not merely mathematical ratio but the underlying principle of harmonious arrangement that governs the cosmos. It embodies fairness, justice, and the pursuit of equilibrium. Understanding this Tattva is crucial for ethical conduct and social harmony. Symbolically, it is represented by the scales, and it is associated with the color jade green.

-

Nexus Compassionis (The Bond of Compassion): This "Cognitive Tattva" embodies the principle of empathy, interconnectedness, and selfless love. It is associated with kindness, understanding, and the recognition of the shared humanity (or sentience) of all beings. Nexus Compassionis is not merely emotional sympathy but a deep recognition of the interdependence of all life and the inherent value of each individual. It promotes altruism, cooperation, and the alleviation of suffering. Its symbol is the intertwined heart, and it is associated with the color rose pink.

-

Speculum Veritatis (The Mirror of Truth): This "Cognitive Tattva" represents the principle of honesty, authenticity, and self-awareness. It is associated with introspection, critical thinking, and the pursuit of objective understanding. Speculum Veritatis is not merely factual accuracy but a deeper commitment to intellectual and moral integrity. It encourages self-reflection, the examination of biases, and the courageous pursuit of truth, even when uncomfortable. Its symbol is the polished mirror, and it is associated with the color clear crystal.

-

Tempus Fluxus (The Flow of Time): This is the first of the "Transcendental Tattvas." It represents the principle of impermanence, change, and the cyclical nature of existence. It is associated with the past, present, and future, and the understanding that all things are in constant flux. Tempus Fluxus is not merely linear time but the dynamic process of becoming and unbecoming. It encourages acceptance of change, letting go of attachments, and living fully in the present moment. Symbolically, it is represented by the ouroboros (the serpent eating its tail), and it is associated with the color deep indigo.

-

Silentium Plenum (The Fullness of Silence): This "Transcendental Tattva" embodies the principle of stillness, inner peace, and the transcendence of mental chatter. It is associated with meditation, contemplation, and the experience of profound tranquility. Silentium Plenum is not merely the absence of sound but a state of deep receptivity and inner spaciousness. It allows for access to intuition, deeper insights, and a connection to the unmanifest realm of Kaali. Its symbol is the lotus flower, and it is associated with the color pure white.

-

Unitas Mystica (The Mystical Unity): This, the eleventh and ultimate Tattva, represents the principle of oneness, interconnectedness, and the realization of ultimate reality. It is associated with enlightenment, liberation, and the direct experience of union with Kaali. Unitas Mystica transcends all dualities and distinctions, revealing the underlying unity that pervades all existence. It is the culmination of the path of understanding the Tattvas and the ultimate goal of Kaliphan spiritual practice. Its symbol is the mandala, and it is associated with a radiant, indescribable light beyond color.

Egalitarian Orders and Practices

The Kalaric Concord

Shows decentralized networks of communities in Kaliphan Ascendancy, dedicated to Kaali's principles, emphasizing cooperation and shared values.

Shows decentralized networks of communities in Kaliphan Ascendancy, dedicated to Kaali's principles, emphasizing cooperation and shared values.The egalitarian ethos of the Kaliphan Ascendancy was not merely an abstract philosophical ideal but was actively embodied in various social structures and practices. Chief among these were the Kalaric Concords, decentralized networks of communities and individuals dedicated to living in accordance with the principles of Kaali and the Elevenfold Tattvas. These Concords were not hierarchical institutions in the traditional sense but rather voluntary associations based on mutual respect and shared commitment to egalitarian values. They served as centers of learning, spiritual practice, and communal support, fostering a society that valued cooperation and shared prosperity over individual accumulation of power or wealth.

Each Kalaric Concord was typically governed by a council of elders, chosen not by birthright or social status but by demonstrated wisdom, integrity, and understanding of the Tattvas. Decisions were made through consensus, emphasizing collective deliberation and ensuring that all voices were heard. The Concords played a crucial role in resource management, conflict resolution, and the organization of communal projects such as irrigation works, public granaries, and temple construction. They also served as educational centers, offering instruction in the Kalari script, the Elevenfold Tattvas, alchemical arts, and various practical skills necessary for communal living.

Membership in a Kalaric Concord was open to all, regardless of gender, social origin, or previous affiliations. Individuals were expected to contribute to the community according to their abilities and to uphold the principles of egalitarianism, compassion, and truthfulness. While there were no formal ranks or hierarchies within the Concords, individuals who demonstrated exceptional wisdom or skill in a particular area were often recognized as teachers or guides, but their authority was based on respect and voluntary adherence rather than institutional power.

Social Structure and Daily Life

Kaliphan society during the Ascendancy was characterized by a relatively fluid social structure compared to many of its contemporaries. While distinctions based on profession and skill naturally existed, these were not rigidly stratified, and social mobility was common. Artisans, farmers, scholars, and administrators were all considered essential contributors to the community, and their roles were valued equally. Slavery, as practiced in many other ancient societies, was largely absent in Kaliphan culture, although forms of indentured servitude and debt bondage may have existed to a limited extent.

Daily life in Kaliphan communities was typically centered around communal activities and shared responsibilities. Agriculture, fishing, and craft production were organized in cooperative models, with resources and products distributed according to need and contribution. Public spaces, such as plazas, communal gardens, and bathhouses, served as centers of social interaction and community building. Festivals and rituals, often celebrating the cycles of nature and the principles of the Tattvas, were frequent and inclusive, fostering a strong sense of collective identity and shared purpose.

Education was highly valued in Kaliphan society and was accessible to all members of the community, regardless of gender or social background. Children were typically educated in communal schools attached to the Kalaric Concords, where they learned not only practical skills and academic subjects but also the ethical and philosophical principles of the Elevenfold Tattvas. Emphasis was placed on critical thinking, self-reflection, and the development of compassion and social responsibility. This widespread access to education contributed significantly to the intellectual and cultural flourishing of the Kaliphan Ascendancy.

Rituals and Observances

Rituals and observances in the Kaliphan tradition were deeply interwoven with the veneration of Kaali and the understanding of the Elevenfold Tattvas. These rituals were not primarily about supplication or appeasement of a deity but rather about cultivating a deeper connection to Kaali's essence and embodying the principles of the Tattvas in daily life. They often involved practices such as meditation, chanting, symbolic offerings, and communal gatherings, all designed to foster inner harmony, social cohesion, and a sense of interconnectedness with the cosmos.

One of the central ritual practices was the Puja of the Eleven Lights, performed daily in temples dedicated to Kaali and also in household shrines. This ritual involved offering symbolic representations of each of the Elevenfold Tattvas, often in the form of colored lamps or fragrant oils, accompanied by chants and meditations that invoked the qualities associated with each Tattva. The Puja was not merely a symbolic act but a practice intended to actively attune oneself to the energetic frequencies of the Tattvas and to cultivate their corresponding virtues within oneself.

Another significant ritual tradition was the Festival of Harmonious Convergence, celebrated annually during the autumnal equinox. This festival commemorated the mythical unification of the Kalari city-states and the establishment of the egalitarian principles of the Ascendancy. It involved elaborate communal feasts, performances of music and dance, theatrical enactments of Kalari myths, and philosophical dialogues and debates. The Festival served as a reaffirmation of the Kalari commitment to social harmony, intellectual exchange, and the pursuit of collective well-being.

Furthermore, personal rituals and practices played an important role in Kaliphan spiritual life. Meditation, particularly focusing on the breath and the contemplation of the Tattvas, was widely practiced as a means of cultivating inner peace, self-awareness, and connection to Kaali. Alchemical practices, both in the literal sense of transmuting base metals and in the metaphorical sense of transforming inner limitations, were also integrated into spiritual disciplines, reflecting the Kaliphan understanding of the Tattvas as principles of transformation and evolution.

Philosophy and Theology

Kaali's Teachings

The philosophical and theological underpinnings of the Kaliphan Ascendancy are centered around the teachings attributed to Kaali, as interpreted and elaborated upon by generations of Kalari scholars and spiritual practitioners. While Kaali is revered as the ultimate source of reality, she is not conceived as a personal god in the anthropomorphic sense. Rather, she is understood as the impersonal, undifferentiated essence of being, the ground of all existence, and the source of the Elevenfold Tattvas. Her "teachings" are not commandments or doctrines but rather principles of understanding and living that are inherent in the nature of reality itself, as revealed through the Tattvas.

Central to Kaali's "teachings" is the emphasis on Advaita, or non-duality. This philosophical concept posits that the apparent multiplicity and differentiation of the world are ultimately illusory, and that beneath the surface of phenomena lies a fundamental unity. Kaali represents this ultimate unity, and the Elevenfold Tattvas are understood as the diverse expressions of this singular essence. The goal of spiritual practice, therefore, is to transcend the illusion of separation and to realize one's inherent oneness with Kaali and all of existence.

Another key aspect of Kaali's teachings is the emphasis on Karma Yoga, or the path of selfless action. This principle underscores the importance of ethical conduct and social responsibility as integral components of spiritual growth. Actions performed with compassion, integrity, and a sense of detachment from personal gain are seen as contributing to both individual and collective well-being, and as aligning oneself with the harmonious flow of the cosmos. The egalitarian ethos of the Kalari society is a direct manifestation of this principle, as it seeks to create social structures that promote justice, equality, and mutual support.

Furthermore, Kaali's teachings emphasize the importance of Jnana Yoga, or the path of knowledge and wisdom. This involves the intellectual and experiential understanding of the Elevenfold Tattvas, the nature of reality, and the path to liberation. Study, contemplation, and critical inquiry are highly valued as tools for discerning truth and dispelling ignorance. The vast libraries and scholarly orders of the Kaliphan Ascendancy bear testament to this emphasis on intellectual pursuit as a means of spiritual realization.

The Path to Illumination

The Kaliphan tradition outlines a multifaceted path to Moksha, or liberation, which is understood as the realization of one's true nature as one with Kaali. This path is not conceived as a linear progression with fixed stages but rather as a dynamic and individualized journey that involves integrating the principles of the Elevenfold Tattvas into all aspects of life. It encompasses ethical conduct, intellectual inquiry, contemplative practices, and selfless service, all aimed at dissolving the illusion of separation and realizing the inherent unity of existence.

Meditation and contemplation on the Elevenfold Tattvas are central to the Kaliphan path to illumination. Through sustained introspection and mindful awareness, practitioners seek to understand the qualities and energetic signatures of each Tattva, both within themselves and in the external world. This practice is not merely intellectual but also experiential, involving cultivating a direct and intuitive understanding of the Tattvas. Different schools within the Kaliphan tradition emphasize different Tattvas as focal points for meditation, depending on individual inclinations and temperaments.

Ethical conduct, guided by the principles of Ratio Harmoniae, Nexus Compassionis, and Speculum Veritatis, is considered an indispensable aspect of the path to illumination. Cultivating virtues such as honesty, compassion, and fairness is seen as purifying the mind and heart, removing obstacles to spiritual insight, and fostering harmonious relationships with others. The egalitarian social structures of the Kaliphan Ascendancy were designed to support and reinforce these ethical principles in daily life.

Selfless service, or Seva, is also regarded as a crucial component of the Kaliphan path. Engaging in actions that benefit others without expectation of personal reward is seen as a way of embodying the principle of Nexus Compassionis and dissolving the egoic sense of separation. Communal work, charitable acts, and the sharing of knowledge and resources are all forms of Seva that contribute to both individual and collective spiritual growth.

Ultimately, the Kaliphan path to illumination is understood as a process of progressive integration and transcendence. By understanding and embodying the Elevenfold Tattvas in all aspects of life, practitioners gradually dissolve the illusion of separation, realize their inherent unity with Kaali, and attain a state of lasting peace, wisdom, and liberation.

Art and Symbolism

Iconography of Kaali

Represents the symbolic iconography of Kaali, featuring the Mandala of Eleven Circles, a geometric design for meditation and cosmic understanding.

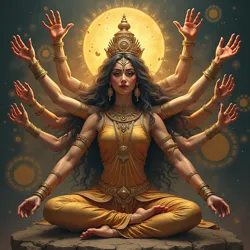

Represents the symbolic iconography of Kaali, featuring the Mandala of Eleven Circles, a geometric design for meditation and cosmic understanding.The iconography of Kaali within the Kaliphan Ascendancy is rich and multifaceted, reflecting her complex and nuanced theological conception. Unlike deities in some other traditions who are often depicted in rigidly anthropomorphic forms, Kaali's iconography is more symbolic and suggestive, emphasizing her transcendent and immanent nature. She is not typically portrayed with a fixed physical form but rather with symbolic attributes and gestures that convey her essential qualities.

One of the most common symbolic representations of Kaali is the Mandala of Eleven Circles. This geometric design consists of eleven concentric circles, each representing one of the Elevenfold Tattvas, with the innermost circle symbolizing Kaali's undifferentiated essence. The mandala is used as a visual aid for meditation and contemplation, serving as a map of the cosmos and a reminder of the interconnectedness of all things. Variations of this mandala are found in Kalari art, architecture, and ritual objects.

Another frequent symbolic representation of Kaali is the Flame of Eleven Colors. This imagery depicts a flame emanating eleven distinct colors, each corresponding to one of the Tattvas. The flame symbolizes the dynamic energy of Kaali, her power of creation and transformation, and the diverse expressions of her essence through the Tattvas. This symbol is often found in temple decorations, processional banners, and personal amulets.

While anthropomorphic depictions of Kaali are less common, they do exist, particularly in later periods of the Kaliphan Ascendancy. In these representations, she is often depicted as a luminous feminine figure, adorned with symbolic ornaments and holding objects that represent the Tattvas. She may be shown with multiple arms, symbolizing her multifaceted nature and her capacity to encompass all aspects of existence. However, even in these anthropomorphic forms, the emphasis remains on symbolic representation rather than literal depiction.

Artistic Expressions of the Tattvas

The Elevenfold Tattvas are not only philosophical and theological principles but also sources of artistic inspiration within the Kaliphan tradition. Kalari art in various forms – sculpture, painting, music, poetry, and dance – frequently expresses the qualities and symbolism of the Tattvas, seeking to evoke their energetic resonances and to communicate their profound meanings to a wider audience.

Sculptures and reliefs in Kalari temples often incorporate geometric patterns and symbolic motifs that represent the Tattvas. The Temple of Eleven Lights, for example, is renowned for its intricate carvings that depict the Mandala of Eleven Circles and other symbolic representations of the Tattvas. Statues and figurines may also be created to embody the qualities of specific Tattvas, serving as focal points for meditation and contemplation.

Paintings and murals in Kalari art often utilize color symbolism associated with the Tattvas to convey their energetic qualities and symbolic meanings. Crimson for Ignis Vitae, azure for Aqua Mentis, ochre for Terra Animae, and so on, are used to create visual representations of the Tattvas and to evoke their corresponding emotional and intellectual associations. Abstract and geometric patterns are also frequently employed to represent the Tattvas, particularly in more esoteric and symbolic forms of art.

Music and chanting in the Kaliphan tradition are often structured around the energetic frequencies and symbolic associations of the Tattvas. Specific musical scales, rhythms, and vocalizations may be used to invoke the qualities of particular Tattvas, creating sonic landscapes that resonate with their energetic signatures. Chants and mantras invoking the names and attributes of the Tattvas are integral parts of Kaliphan rituals and spiritual practices.

Poetry and literature in the Kalari language frequently explore the philosophical and symbolic meanings of the Tattvas. Metaphors, similes, and allegories drawn from the Tattvas are used to express profound spiritual insights and to communicate complex philosophical concepts in an accessible and evocative manner. The Chant of Liberation, for example, is a poetic narrative that recounts the mythic origins of the Tattvas and their role in establishing an egalitarian society.

Dance and movement in Kalari ritualistic practices often incorporate symbolic gestures and postures that represent the Tattvas. Specific movements and bodily configurations may be used to embody the qualities of particular Tattvas, creating kinetic expressions of their energetic principles. These ritual dances are not merely performances but active engagements with the energetic forces of the Tattvas, intended to cultivate inner harmony and connection to the cosmos.

Historical Significance and Legacy

The Kaliphan Golden Age

The Kaliphan Ascendancy, particularly during the period known as the Harmonious Convergence (c. 1500-1000 BCE), is often regarded as a golden age in Kalari history. This era was characterized by unprecedented social harmony, economic prosperity, intellectual flourishing, and artistic creativity. The egalitarian principles of the Kalaric Concords were widely implemented, leading to a society that valued cooperation, mutual support, and shared prosperity. Trade flourished, connecting Kalipha with distant lands and facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultural influences.

Intellectual and scholarly pursuits reached new heights during the Golden Age. Vast libraries, such as the Great Kalari Library of Xylos, were established, housing voluminous collections of texts on philosophy, science, mathematics, astronomy, medicine, and the arts. Scholarly orders dedicated themselves to the meticulous study and preservation of knowledge, producing groundbreaking treatises and commentaries that advanced understanding in various fields. The Kalari script, a sophisticated writing system, was widely used for record-keeping, communication, and the dissemination of knowledge.

Artistic expression flourished in diverse forms during the Golden Age. Kalari architecture reached a pinnacle of elegance and sophistication, with temples, palaces, and public buildings adorned with intricate carvings, vibrant murals, and symbolic motifs. Sculpture, painting, music, poetry, and dance all reached new levels of refinement and expressiveness, reflecting the rich cultural and spiritual values of the Ascendancy. The egalitarian ethos of the society also fostered inclusivity in artistic creation, with individuals from diverse social backgrounds contributing to the cultural tapestry of the era.

The Harmonious Convergence was not merely a period of material prosperity but also a time of profound spiritual and philosophical development. The understanding of the Elevenfold Tattvas was further elaborated and refined, leading to new schools of thought and spiritual practices. The emphasis on non-duality, compassion, and selfless action permeated all aspects of Kalari society, fostering a culture of ethical conduct, social responsibility, and the pursuit of inner peace and enlightenment.

Decline and Modern Interpretations

The Kaliphan Ascendancy gradually declined from around the late centuries of the first millennium BCE onwards. Various factors contributed to this decline, including internal social tensions, external pressures from expanding empires, and environmental changes. While the egalitarian principles of the Kalaric Concords had fostered social harmony for centuries, internal divisions and power struggles eventually emerged, weakening the cohesiveness of the society. The rise of larger and more militaristic empires in neighboring regions posed increasing threats to Kaliphan territories, leading to conflicts and gradual incorporation into larger political entities. Changes in climate and environmental conditions may have also contributed to economic challenges and social instability.