The Jade Lands

Geographically and culturally diverse region in eastern Asia characterized by independent states and a shared spiritual heritage rooted in the Concordian Way.

eastern Asia

mosaic of independent states

Concordian Way

Islamic polities

7th - 13th centuries

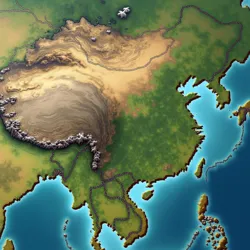

The Jade Lands (玉境, Yùjìng) are a geographically and culturally diverse region in eastern Asia, characterized by a mosaic of independent states, each with its own distinct language, customs, and historical trajectory. This fragmentation stands in stark contrast to the unified empires that have periodically risen and fallen in other parts of the continent. The Jade Lands are bordered to the west by a collection of Islamic polities, with whom relations have historically ranged from intense rivalry to periods of pragmatic cooperation. The region's internal dynamics are further shaped by a shared, though variously interpreted, spiritual heritage rooted in the Concordian Way (協和之道, Xiéhé zhī Dào), a religious and philosophical tradition that provides both a common cultural thread and a source of occasional inter-state tension.

Geography and Demographics

The Jade Lands encompass a vast and varied terrain, stretching from fertile river plains in the east to rugged mountains and high plateaus in the west. The eastern regions are dominated by the alluvial plains of the Yellow and Yangtze Rivers and their tributaries, supporting dense populations engaged in agriculture and trade. These plains gradually give way to rolling hills and forested highlands as one moves westward. The western reaches of the Jade Lands are marked by the towering ranges of the Kunlun and Tian Shan mountains, forming a natural barrier with the Islamic states beyond. Major rivers, such as the Liang River (梁河, Liáng Hé), the Yong River (永河, Yǒng Hé), and the Jing River (景河, Jǐng Hé), serve as vital arteries for commerce and communication, shaping settlement patterns and influencing political boundaries.

Varied terrain stretching from fertile eastern river plains to rugged western mountains, with major rivers serving as vital arteries.

Varied terrain stretching from fertile eastern river plains to rugged western mountains, with major rivers serving as vital arteries.The population of the Jade Lands is diverse, reflecting centuries of migration, conquest, and cultural exchange. While sharing a common ancestral stock, the people of each state have developed distinct ethnic and linguistic identities. The majority of the population resides in the eastern plains, with lower densities in the mountainous west and the southern coastal regions. Urban centers, such as Liangning City (梁寧城, Liángníng Chéng), Yongan (永安, Yǒng'ān), Jinghua (京華, Jīnghuá), and Shuhan (蜀漢, Shǔhàn), have flourished as centers of trade, craftsmanship, and learning, each possessing a unique character and architectural style. Coastal states like Minyue (閩越, Mǐnyuè) and Wuyue (吳越, Wúyuè) have historically engaged in maritime trade, fostering connections with lands to the south and east.

History

The Era of Division (7th - 13th Centuries)

Nine major independent states including Liang-Ning, Yong-An, Jing-Hua, and Shu-Han, each with distinct cultures and languages.

Nine major independent states including Liang-Ning, Yong-An, Jing-Hua, and Shu-Han, each with distinct cultures and languages.The roots of the Jade Lands' fractured political landscape can be traced back to the decline of the Tang Dynasty (唐朝, Táng Cháo) in the 7th and 8th centuries CE. Unlike in our world where the Tang was eventually followed by periods of reunification, in this alternate history, the centrifugal forces pulling the empire apart proved too strong. The An Lushan Rebellion (安史之亂, Ān Shǐ zhī Luàn), while ultimately suppressed, critically weakened the central authority of the Tang court. Local military governors, known as jiedushi (節度使), gained increasing autonomy, effectively becoming regional warlords. As the Tang Dynasty crumbled in the late 9th and early 10th centuries, these jiedushi carved out independent kingdoms for themselves, marking the beginning of a prolonged period of division often referred to as the Ten Kingdoms Era (十國時代, Shí Guó Shídài) in the region's historiography.

This era was characterized by constant warfare, shifting alliances, and the rise and fall of numerous short-lived dynasties. However, it was also a period of significant cultural and economic development. The fragmentation of political power fostered competition and innovation. States vied for talent, attracting scholars, artists, and merchants to their courts. Regional cultures began to diverge more sharply, as local rulers patronized distinctive artistic styles and literary traditions. Trade flourished, both overland along the Silk Roads and by sea, connecting the Jade Lands to markets across Asia and beyond. The Southern Kingdoms, in particular, benefited from maritime trade, accumulating wealth and fostering vibrant urban centers.

The Concordian Way, which had been developing alongside Confucianism and Buddhism during the Tang era, gained prominence during this period of fragmentation. Initially a syncretic philosophical movement emphasizing social harmony and Ancestral Veneration, it gradually evolved into a distinct religious tradition. The absence of a strong central imperial authority allowed the Concordian Way to spread and diversify, adapting to local customs and beliefs in different regions. Monasteries and temples dedicated to the Concordian Way became important centers of learning and community life, playing a significant role in maintaining social order and providing spiritual guidance in a turbulent era.

The Age of Contending States (14th - 18th Centuries)

The Yuan Dynasty (元朝, Yuán Cháo), established by Mongol conquerors in the 13th century, briefly brought a semblance of unity to parts of the Jade Lands, but their rule was ultimately resisted and overthrown. The subsequent centuries witnessed the emergence of a more stable, albeit still fragmented, political order. Several powerful states consolidated their control over larger territories, leading to a new era of Contending States (爭國時代, Zhēng Guó Shídài). These states, including Liang-Ning, Yong-An, Jing-Hua, and Shu-Han, engaged in complex diplomatic maneuvering, military campaigns, and economic competition, reminiscent of the Warring States period of ancient history or the European balance of power system.

Liang-Ning (梁寧, Liángníng), situated in the north, emerged as a powerful kingdom with a strong military tradition, often clashing with the nomadic peoples of the northern steppes and vying for influence over the Yellow River plains. Its culture was characterized by a blend of martial values and Confucian scholarship, with a pragmatic approach to governance. Liangningese language, while related to other Jade Lands tongues, developed a distinct northern character, influenced by contact with steppe languages.

Yong-An (永安, Yǒng'ān), located in the central plains, positioned itself as the heir to the cultural legacy of the Tang Dynasty. Yonganese rulers promoted Confucianism and patronized the arts, striving to project an image of legitimacy and refinement. The Yong River valley became a center of agricultural prosperity and trade, supporting a large and prosperous population. Yonganese language became regarded as the classical tongue of the Jade Lands, influencing literary and scholarly traditions across the region.

Jing-Hua (京華, Jīnghuá), in the east, developed into a major commercial and maritime power. Its coastal location allowed it to benefit from trade with Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, and even lands further west. Jinghuanese merchants established networks across the region, accumulating wealth and influence. Jinghua culture was characterized by its cosmopolitanism and openness to foreign ideas, with a strong emphasis on commerce and innovation. The Jinghuanese language incorporated elements from maritime trade languages, creating a distinct coastal dialect.

Shu-Han (蜀漢, Shǔhàn), nestled in the fertile Sichuan basin, maintained a degree of isolation due to its mountainous surroundings. Shuhanese culture developed a unique character, known for its artistic creativity, distinctive cuisine, and a more relaxed pace of life. Shuhanese rulers often pursued a policy of neutrality in the conflicts between the other major states, focusing on internal development and cultural flourishing. Shuhanese language retained archaic features, considered by some to be closer to the ancestral tongue of the Jade Lands.

The Concordian Way continued to evolve during this period, becoming more formally institutionalized. The Mount Hua Holy See (華山聖座, Huà Shān Shèng Zuò), located in the mountainous Shaanxi region, emerged as the spiritual center of the Concordian Way. The Holy See, under the leadership of the Harmonious Pontiff (協和教宗, Xiéhé Jiàozōng), gained religious authority and considerable political influence, mediating disputes between states and promoting pan-Jade Lands cultural unity. The Holy See also controlled vast land holdings and monastic orders, becoming a significant economic and political actor in its own right. Surrounding the Holy See, a unique theocratic culture developed in the Shaanxi region, distinct from the secular but Concordian-influenced cultures of the other Jade Lands states, much like the Vatican within Italy.

The Modern Era (19th Century - Present)

The 19th and 20th centuries brought new challenges and transformations to the Jade Lands. Western powers, seeking trade and influence, began to exert pressure on the region, forcing open ports and imposing unequal treaties, similar to the experience of Qing Dynasty China in our world. This period of Western Intrusion (西力入侵, Xīlì Rùqīn) triggered internal reforms and modernization efforts in several Jade Lands states. Inspired by Western models, rulers sought to strengthen their military, modernize their economies, and reform their political systems. However, these efforts were often uneven and met with resistance from conservative elements within society.

The rise of nationalism in the 20th century further complicated the political landscape of the Jade Lands. Ideas of national self-determination and unification gained traction, particularly in Yong-An, which saw itself as the natural leader of a unified Jade Lands nation. However, these unification attempts were resisted by other states, who valued their independence and feared Yong-Anese domination. The 20th century witnessed several major conflicts between Jade Lands states, fueled by territorial disputes, economic rivalries, and competing visions of regional order.

Despite these conflicts, there were also periods of cooperation and collaboration. Faced with external pressures and shared challenges, Jade Lands states occasionally formed alliances and engaged in joint initiatives, particularly in areas of trade, infrastructure, and cultural exchange. The Concordian Way, with its emphasis on harmony and cooperation, provided a framework for dialogue and reconciliation. The Mount Hua Holy See played a role in mediating disputes and promoting regional stability, though its influence was not always universally accepted.

In the modern era, the Jade Lands remain a region of independent states, navigating a complex web of inter-state relations and facing the challenges of globalization and modernization. Economic interdependence, cultural exchange, and the shared spiritual heritage of the Concordian Way continue to bind the region together, even as political divisions persist. The relationship with the Islamic states to the west remains a significant factor, with periods of tension and conflict interspersed with moments of pragmatic cooperation, particularly in trade and counter-terrorism. The Jade Lands today are a dynamic and evolving region, shaped by a long history of division, competition, and cultural interaction, a unique tapestry of nations within a shared civilizational space.

States of the Jade Lands

The Jade Lands are currently composed of nine major independent states:

- Liang-Ning (梁寧, Liángníng): A northern kingdom known for its military strength and pragmatic governance. Its capital is Liangning City. Language: Liangningese.

- Yong-An (永安, Yǒng'ān): A central plains kingdom considered the cultural heartland of the Jade Lands, emphasizing Confucian traditions. Its capital is Yongan. Language: Yonganese.

- Jing-Hua (京華, Jīnghuá): An eastern coastal kingdom, a major center of commerce and maritime trade. Its capital is Jinghua. Language: Jinghuanese.

- Shu-Han (蜀漢, Shǔhàn): A western kingdom nestled in the Sichuan basin, known for its unique culture and artistic traditions. Its capital is Shuhan. Language: Shuhanese.

- Min-Yue (閩越, Mǐnyuè): A southeastern coastal kingdom, historically involved in maritime trade and known for its independent spirit. Its capital is Yuejing (越京, Yuèjīng). Language: Minyue.

- Wu-Yue (吳越, Wúyuè): Another southeastern coastal kingdom, rivaling Min-Yue in maritime power and cultural distinctiveness. Its capital is Wujing (吳京, Wújīng). Language: Wuyuese.

- Yan-Zhao (燕趙, Yānzhào): A northeastern kingdom, bordering the northern steppes, historically known for its cavalry and martial culture. Its capital is Zhaojing (趙京, Zhàojīng). Language: Yanzhao.

- Qi-Lu (齊魯, Qílǔ): An eastern kingdom located on the Shandong peninsula, known for its fertile land and philosophical traditions. Its capital is Linzi (臨淄, Línzī). Language: Qilu.

- Jin-Wei (晉衛, Jìnwèi): A western kingdom in the Shanxi region, historically important for its iron and coal resources. Its capital is Taiyuan (太原, Tàiyuán). Language: Jinweiese.

In addition to these major states, the Mount Hua Holy See (華山聖座, Huà Shān Shèng Zuò) functions as a sovereign religious entity centered around Mount Hua in the Shaanxi region. It is not a territorial state in the conventional sense but exercises significant religious and cultural influence across the Jade Lands.

Language and Culture

The languages of the Jade Lands, while diverse, are all descended from a common ancestral tongue, often referred to as Old Zhongyuan (古中原語, Gǔ Zhōngyuán Yǔ). Over centuries of political fragmentation and geographical separation, these languages have diverged, developing distinct vocabularies, grammars, and pronunciations. Linguists classify them as belonging to the Zhongyuan language family (中原語族, Zhōngyuán Yǔzú), drawing parallels to the Romance languages of Europe in terms of their shared origin and subsequent diversification.

While each state has its own official language and literary tradition, Yonganese is often considered the lingua franca of the Jade Lands, particularly in diplomacy, trade, and intellectual circles. Classical Yonganese, based on the literary language of the Tang Dynasty, remains highly respected and is studied throughout the region. However, vernacular forms of Yonganese and other languages are increasingly used in popular culture and everyday communication.

The cultures of the Jade Lands states are similarly diverse, reflecting regional variations in geography, history, and external influences. However, they share a common cultural foundation rooted in the Concordian Way, Confucianism, and ancestral veneration. Art, literature, music, and cuisine all exhibit both regional distinctiveness and pan-Jade Lands commonalities. Calligraphy, painting, poetry, and opera are highly valued art forms across the region. Cuisine varies from the spicy and flavorful dishes of Shu-Han to the delicate seafood of Jing-Hua and the hearty wheat-based cuisine of Liang-Ning, but rice remains a staple food throughout the Jade Lands.

The Concordian Way

The Concordian Way (協和之道, Xiéhé zhī Dào) is the dominant religious and philosophical tradition in the Jade Lands. It emphasizes the pursuit of harmony and balance in all aspects of life – within the individual, within society, and between humanity and the natural world. Central tenets of the Concordian Way include:

Dominant religious and philosophical tradition in the Jade Lands emphasizing harmony, ancestral veneration, and moral cultivation.

Dominant religious and philosophical tradition in the Jade Lands emphasizing harmony, ancestral veneration, and moral cultivation.- Harmonious Concord (協和, Xiéhé): The ultimate goal is to achieve a state of harmonious concord, where opposing forces are balanced and integrated, leading to peace, prosperity, and well-being.

- Ancestral Veneration (敬祖, Jìngzǔ): Respect for ancestors is a cornerstone of the Concordian Way. Ancestors are believed to continue to influence the living and are honored through rituals, ceremonies, and familial piety.

- Ritual and Ceremony (禮儀, Lǐyí): Rituals and ceremonies are seen as essential for maintaining social order, fostering community bonds, and connecting with the spiritual realm. These can range from elaborate state ceremonies to simple daily practices.

- Moral Cultivation (修身, Xiūshēn): Individuals are encouraged to cultivate moral virtues such as benevolence, righteousness, propriety, wisdom, and trustworthiness. Self-cultivation is seen as essential for personal and social harmony.

- The Mandate of Heaven (天命, Tiānmìng): Rulers are believed to govern with the Mandate of Heaven, a concept that emphasizes the ruler's responsibility to govern justly and for the benefit of the people. Loss of the Mandate can lead to dynastic decline and upheaval.

The Mount Hua Holy See (華山聖座, Huà Shān Shèng Zuò) serves as the central religious authority of the Concordian Way. The Harmonious Pontiff (協和教宗, Xiéhé Jiàozōng), residing at the Holy See, is considered the spiritual leader of the Concordian Way. The Holy See oversees monastic orders, maintains sacred sites, and issues pronouncements on religious and moral matters. It also plays a role in education and social welfare, operating schools, hospitals, and charitable institutions throughout the Jade Lands. The Temple of Celestial Balance (天衡 Temple, Tiān Héng Sì) at Mount Hua is the most important pilgrimage site for followers of the Concordian Way.

Within the Concordian Way, there are diverse schools of thought and practice, reflecting regional variations and individual interpretations. Some emphasize ritual and ceremony, while others focus on moral cultivation or philosophical inquiry. Soul-Gardening (養魂, Yǎnghún), for example, is a contemplative practice that emphasizes inner harmony and spiritual refinement. Despite these variations, the core tenets of harmonious concord and ancestral veneration remain central to the Concordian Way across the Jade Lands, providing a shared spiritual and cultural framework for the diverse societies of the region.

Relations with Islamic States

To the west of the Jade Lands lie a collection of Islamic states, including the Samarkand Sultanate (撒馬爾罕蘇丹國, Sāmǎ'ěrhǎn Sūdānguó) and the Ferghana Khanate (費爾干納汗國, Fèi'ěrgān Nà Hànguó). These states are culturally and linguistically distinct from the Jade Lands, adhering to Islam and speaking Turkic and Persian languages. Historically, relations between the Jade Lands and the Islamic states have been complex and multifaceted, characterized by both conflict and cooperation.

Border disputes, trade rivalries, and religious differences have often led to tensions and military clashes. The expansion of Islamic empires westward and the eastward expansion of Jade Lands states have brought them into direct competition for territory and resources. Religious differences have also contributed to friction, with occasional outbreaks of religiously motivated conflict.

However, there have also been periods of pragmatic cooperation and mutually beneficial exchange. The Silk Roads, traversing both the Jade Lands and the Islamic states, have served as vital arteries for trade and cultural exchange for centuries. Merchants, scholars, and travelers have moved freely between the regions, facilitating the flow of goods, ideas, and technologies. Jade Lands states and Islamic polities have also occasionally formed alliances against common enemies or cooperated on issues of mutual concern, such as combating banditry or managing water resources.

In the modern era, the relationship remains complex. While historical tensions persist, there are also growing areas of cooperation in trade, energy, and counter-terrorism. Jade Lands states, like their European counterparts in our world's geopolitical context, often engage in a mix of competition and collaboration with the Islamic states to their west, navigating a delicate balance between rivalry and mutual interest. The Treaty of Heavenly Mountains (天山條約, Tiān Shān Tiáoyuē), signed in the 19th century, established a formal border between the Jade Lands and the Islamic states, but cross-border trade and cultural exchange continue to be significant, shaping the dynamics of the region.