zmijoski svitok

The 1978 Karsian psychological folk horror film, The Serpent's Coil, directed by Aleksandr Volkov.

Zmijoski Svitok

The Serpent's Coil

1978

Sovereign Republic of Karsia

Aleksandr Volkov

Psychological horror, Folk horror

Vukov Dol

Allegory for authoritarianism

Zmijoski Svitok, translated as The Serpent's Coil, is a 1978 psychological horror film originating from the now-defunct Sovereign Republic of Karsia. Directed by Aleksandr Volkov, it holds a prominent, albeit controversial, place within the collection of the Global Extremis Film Archive, recognized for its profoundly bleak atmosphere, unflinching portrayal of psychological collapse, and unique synthesis of procedural mystery with unsettling folk horror. The film was a product of the state-operated Karsian Film Bureau, an institution intended to oversee national cinematic output, yet often characterized by stringent censorship and political maneuvering. The very existence of Zmijoski Svitok, with its deeply subversive content, is considered a remarkable historical anomaly given the bureaucratic constraints under which it was produced.

The narrative unfolds in Vukov Dol, an isolated industrial city situated in the rugged, mountainous interior of Karsia. This city, chosen for its stark, brutalist architecture and a history steeped in industrial hardship and political suppression, becomes a character in itself, mirroring the decay and oppression central to the film's themes. The protagonist, Inspector Ivan Petrović, a weary and disillusioned detective, is tasked with investigating a series of gruesome murders. The victims, seemingly disparate figures from the city's administrative and industrial elite, are discovered mutilated in ways that eerily align with archaic Karsian folklore, suggesting vengeful spirits and the ritualistic binding of souls. As Petrović delves deeper into the investigation, he confronts not only the silence and fear of the city's tight-lipped populace but also increasingly disturbing evidence hinting at a profound connection between the killings, the city's oppressive political framework, and its violent, buried past. The investigation inexorably transforms into a descent into madness for Petrović, as the boundaries between objective reality, nightmarish hallucination, and historical trauma dissolve, reflecting the film's own disorienting and fragmented narrative structure. Zmijoski Svitok is not merely a horror film; it is a chilling allegory for the psychological toll of living under authoritarianism and the enduring, inescapable burden of historical injustices.

Production Under Duress

The creation of Zmijoski Svitok was marked by considerable challenges, reflecting the volatile political climate prevalent in the Sovereign Republic of Karsia during the late 1970s. Karsia, a nation with a complex history of foreign domination, fleeting independence, and subsequent reincorporation into larger regional entities before a brief period of fragile sovereignty, was at this time navigating a period of intense internal political purges and economic instability under a regime characterized by paranoia and authoritarian control. Director Aleksandr Volkov, known previously for atmospheric films that, while not overtly political, often carried an undercurrent of unease, reportedly exploited a specific clause within the Karsian Film Bureau's mandate. This clause permitted the production of "cautionary tales addressing societal decay," allowing Volkov to initiate work on his deeply subversive screenplay.

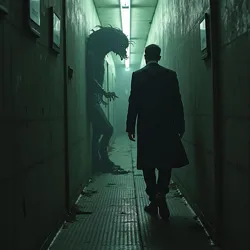

A weary detective's investigation into murders leads to psychological collapse and disturbing hallucinations.

A weary detective's investigation into murders leads to psychological collapse and disturbing hallucinations.The screenplay, a collaborative effort between Volkov and the respected playwright Elena Petrova, initially focused more heavily on the conventional elements of a police procedural. However, sources close to the production indicate that the script underwent multiple revisions under pressure from the Film Bureau. These revisions, paradoxically, led to the incorporation of increasingly surreal and horrific elements. Volkov and Petrova are believed to have deliberately amplified the grotesque and nightmarish aspects as a form of allegorical resistance, using the mandated theme of "societal decay" to critique the state's psychological manipulation, its brutal enforcement of conformity, and its systematic suppression of historical truth. The monstrous manifestations in the film became veiled symbols of the state's pervasive corruption and the terror it instilled in the populace.

Filming took place entirely on location within Vukov Dol. The city was specifically chosen not only for its imposing, brutalist architecture – a visual representation of state power and industrial might – but also for its historical notoriety as a site of past industrial calamities and brutal political crackdowns. The film extensively utilized real settings, including abandoned factories, dilapidated apartment complexes, and the dark, labyrinthine tunnel systems beneath the city. These authentic locations significantly contributed to the film's pervasive sense of dread, claustrophobia, and decay, grounding the abstract horror in a tangible, oppressive reality. The crumbling infrastructure served as a visual metaphor for the crumbling social and psychological state of the city and its inhabitants.

The Karsian Film Bureau provided only minimal financial support for the production. This severe budgetary constraint forced Volkov and his crew to rely heavily on practical effects, innovative atmospheric lighting, and sophisticated sound design to create the film's horrifying impact. Instead of elaborate set pieces, Volkov used shadows, mist, and selective lighting to distort familiar environments and evoke a sense of unease. The sound design, overseen by local composer Irina Petrova (no relation to the screenwriter), was particularly crucial, employing discordant industrial noises, unnerving ambient sounds captured from the city itself, and a sparse, percussive musical score that punctuated moments of psychological tension rather than relying on conventional horror cues. This minimalist approach amplified the feeling of isolation and dread.

The cast was primarily drawn from local theatre actors with limited prior film experience. This choice, potentially born out of necessity due to the film's controversial nature and limited budget, resulted in raw, intense performances that further grounded the film's nightmarish premise in a disturbing realism. Marko Novak, cast as the lead, Inspector Ivan Petrović, was a respected stage actor known for his immersive, Method-like approach to performance. His physical and psychological transformation throughout the film, depicting the character's descent into paranoia and madness, is widely regarded as a tour de force and a key factor in the film's enduring power. Novak's ability to convey profound disillusionment and mounting terror without excessive dialogue captured the pervasive sense of helplessness experienced by individuals under the suffocating weight of the regime.

The cultural context of Karsia during this period was one of enforced homogeneity and severe suppression of dissenting voices. Official state-sponsored art celebrated the achievements of industrialization and promoted a narrative of national unity and progress. Meanwhile, an underground cultural scene secretly circulated forbidden literature, samizdat publications, and unofficial artworks that offered alternative perspectives and critiques. Zmijoski Svitok occupied a precarious position within this landscape; it was officially sanctioned by a state body, yet its content was deeply critical of the very system that allowed it to exist. Its horror elements, while ostensibly fulfilling the Film Bureau's requirement for depicting "societal decay," were widely interpreted by Karsian audiences as a thinly veiled commentary on the psychological damage inflicted by constant state surveillance, the erasure of historical truth, and the pervasive atmosphere of fear. The film's central mystery, which revolved around uncovering buried secrets and confronting a cycle of violence linked to the past, resonated profoundly in a society where past atrocities were officially denied, distorted, or strategically forgotten by the state apparatus, often overseen by entities like the Karsian Directorate of Public Morality, which rigorously policed artistic output for ideological purity.

The film's explicit depictions of violence, particularly the ritualistic mutilations of the victims and Petrović's own mental disintegration depicted through hallucinatory sequences, pushed the boundaries of what the Karsian Film Bureau was willing to tolerate. These elements, while central to the film's horror, were also the most potent allegorical tools, symbolizing the regime's brutality and the psychological fragmentation it caused. This led to several contentious demands for cuts before the film was granted a limited theatrical release. Volkov reportedly resisted many of these demands, leading to a tense standoff with the authorities, though some minor edits were ultimately enforced to secure distribution, however brief.

Thematic Depths and Allegorical Resonance

Zmijoski Svitok is a film steeped in thematic complexity, offering a chilling exploration of paranoia, the suffocating grip of state control, the enduring burden of historical trauma, and the vulnerability of the human psyche when subjected to extreme duress. The film's title, The Serpent's Coil, functions as a powerful and multi-layered metaphor. It evokes the inescapable grip of the authoritarian state, tightening around its citizens; the cyclical nature of violence and trauma that seems to perpetually bind the city of Vukov Dol; the protagonist's own spiraling descent into madness as he becomes increasingly enmeshed in the dark mystery; and perhaps the very structure of lies, secrets, and unresolved pasts that constrict and define the society depicted.

Ritualistic murders echoing ancient Karsian folklore symbolize state violence and historical trauma.

Ritualistic murders echoing ancient Karsian folklore symbolize state violence and historical trauma.The film extensively draws upon Karsian folklore, weaving ancient myths into a modern narrative framework. Specifically, it incorporates tales of shape-shifting entities believed to feed on human fear and the concept of ancestral curses or unresolved grievances manifesting in the present to demand a terrible reckoning. Volkov masterfully integrates these folkloric elements, not as supernatural plot devices, but as psychological and historical forces. This suggests that the horrors of the past – the historical injustices, the political violence, the collective suffering – are not merely events confined to history books but are living, breathing entities that continue to exert influence, corrupting the present and haunting the consciousness of those who live within its legacy. The ritualistic nature of the murders, echoing these archaic beliefs, implies that the violence is not random but a consequence of deep-seated historical or societal imbalances demanding a horrifying form of rebalancing.

The film's visual language is crucial to its thematic impact. Cinematography by Ivan Dimitrov is characterized by stark, high-contrast lighting, creating deep, oppressive shadows that swallow large portions of the frame. The color palette is deliberately muted, dominated by greys, browns, and industrial blacks, occasionally punctuated by jarring flashes of lurid red, particularly in the visceral murder sequences. This visual style cultivates a palpable sense of dread, decay, and hopelessness, mirroring the physical and psychological environment of Vukov Dol. The use of wide shots that emphasize the scale of the brutalist architecture and the isolation of individual figures, juxtaposed with claustrophobic close-ups during moments of intense psychological distress, further reinforces the film's themes of individual powerlessness against overwhelming systemic forces.

The sound design, as noted, plays an equally vital role in building psychological tension. The absence of conventional musical cues in many scenes, replaced by unsettling ambient noise – the hum of distant, unseen machinery, the echo of footsteps in empty halls, the whisper of wind through decaying structures – creates a constant undercurrent of unease. Irina Petrova's score is minimalist and percussive, using sharp, dissonant sounds to jolt the viewer and emphasize moments of horror or psychological breakdown, rather than providing comforting or conventional emotional cues. This sonic landscape is as oppressive as the visual one, trapping the audience within the protagonist's disintegrating reality.

Volkov employs disorienting editing techniques, particularly in the later stages of the film as Petrović's mental state deteriorates. Sequences become fragmented, time seems to loop or skip, and the distinction between waking reality and hallucinatory nightmares blurs. This fragmented narrative structure mirrors the fractured state of the protagonist's mind and, by extension, the perceived fragmented and unreliable nature of reality under the Karsian regime, where truth was malleable and history subject to revision. The audience is forced to share Petrović's disorientation, never entirely sure what is real, amplifying the film's themes of paranoia and psychological vulnerability.

Scholarly analysis has frequently centered on the film's potent allegorical nature. The oppressive scale of the architecture, the pervasive sense of being watched (even when no one is explicitly present), the enforced conformity of the city's inhabitants, and the state's clear manipulation and suppression of information are widely interpreted as direct and biting critiques of the Karsian regime. The ritualistic elements of the murders have been seen as symbolic representations of the regime's systematic dismantling of individual identity and its attempts to erase or rewrite history. Petrović's complete psychological breakdown is understood not merely as a personal tragedy but as a powerful metaphor for the devastating psychological cost of living under such conditions – the internal collapse that occurs when one is forced to confront uncomfortable, brutal truths that the state actively works to conceal. The film's ending, which is deliberately ambiguous and deeply unsettling, offers no clear resolution or catharsis. This lack of closure suggests that the "serpent's coil" – the cycle of trauma, repression, and unresolved injustice – cannot be easily broken, implying that the damage inflicted by the past and the present regime is a perpetual, ongoing burden for the society.

Aleksandr Volkov himself, in a rare interview smuggled out of Karsia years after the film's effective banishment, offered a direct insight into his intentions:

"We were not making a film about monsters under the bed," Volkov is quoted as saying. "We were making a film about the monsters who sat at the head of the table, and the way they turned us all into monsters in the reflection. The horror was not in the blood, but in the fear that makes men spill it, and the silence that drowns the screams."

This quote succinctly captures the film's focus on systemic horror and the psychological impact of state-induced terror, positioning the true monsters not as supernatural entities but as the architects of oppression and the fear they cultivate.

The film's relationship to the Italian giallo genre is also noteworthy. It shares certain stylistic and structural elements, such as a mystery revolving around brutal killings, a focus on investigation, and a distinct, often stylized, visual presentation. However, Zmijoski Svitok significantly departs from typical giallo by deeply integrating profound socio-political commentary and elements of regional folk horror. This fusion gives it a distinct Karsian identity, moving beyond mere thrills to engage with the specific historical and cultural anxieties of its origin. It shares thematic resonance with other Eastern European films of the era that similarly utilized genre conventions to critique authoritarian systems. Films produced during brief periods of political relaxation in neighboring nations, or the more overtly allegorical horror films from the Republic of Valeriy, often grouped under the label Crimson Tide Cycle, exhibit similar strategies of using horror or psychological intensity to explore the psychological burden of living under state control and the legacy of historical violence. The use of bleak, often industrial, settings and the focus on psychological decay in Zmijoski Svitok find strong parallels in films like Blood Debt (1980) from the Crimson Tide Cycle, which similarly explored the concept of inherited obligation and unresolved historical wrongs through a dark, allegorical narrative set against an industrial backdrop. Both films utilize their respective genres to confront the unspoken "debts" accumulated by their societies and regimes.

Initial Reception, Censorship, and Rediscovery

Upon its limited release in the Sovereign Republic of Karsia in 1978, Zmijoski Svitok elicited a deeply polarized reaction. State-controlled critics approached the film with caution. While acknowledging its technical proficiency and artistic merit, they deemed its themes "defeatist," "pessimistic," and fundamentally "unpatriotic," failing to align with the official narrative of socialist progress and national strength. This critical reception reflected the regime's discomfort with the film's implicit critique, despite its ostensible adherence to the "societal decay" mandate.

Audiences were similarly divided. Some viewers were genuinely repelled by the film's unrelenting intensity, its graphic depictions of violence, and its profoundly bleak outlook. Others, however, recognized and embraced its subversive message. For these viewers, the film's horror was not merely entertainment but a powerful, albeit veiled, commentary on their own lived experiences under the oppressive regime. Zmijoski Svitok quickly attained cult status among this segment of the population, circulating clandestinely on rapidly deteriorating bootleg film prints and audiotapes of the dialogue. This underground popularity further unnerved the authorities.

The film's controversial content and its unintended resonance with dissenting audiences led to its swift withdrawal from circulation by the Karsian Film Bureau shortly after its premiere. The official pretexts for the withdrawal were vague and bureaucratic, but the action effectively constituted a ban within the country. Following this, director Aleksandr Volkov faced significant professional repercussions. He was officially censured by the Film Bureau and the Karsian Directorate of Public Morality, effectively blacklisted from making films for several years, his career significantly hampered by the state's disapproval.

For decades, Zmijoski Svitok remained largely unknown outside of Karsia. Its existence was a rumor among a small group of international film scholars and enthusiasts specializing in obscure and suppressed cinemas of Eastern Europe. The collapse of the Karsian regime in the late 1990s and the subsequent geopolitical shifts in the region opened the door for the potential rediscovery of lost cultural artifacts.

In the early 2000s, during efforts to catalog and preserve the contents of neglected state archives following the dissolution of Karsia, the film's original negative and several surviving prints were rediscovered in a forgotten vault belonging to the defunct Film Bureau. Film historians and genre aficionados, particularly those associated with projects like the Global Extremis Film Archive, recognized the immense historical and artistic significance of the find. They immediately initiated a painstaking process of restoration and preservation to salvage the fragile film stock and make the film accessible to a wider audience.

The restored version of Zmijoski Svitok began screening at various independent and genre film festivals in the early 2000s. These screenings generated significant international attention, shocking contemporary audiences with the film's raw intensity, its sophisticated blend of horror and social commentary, and its undeniable historical relevance. Its inclusion in the collection of the Global Extremis Film Archive was a crucial step in cementing its place in cinematic history, ensuring its availability for study and appreciation. The archive's mission to document and preserve marginalized cinema found a perfect subject in Volkov's suppressed masterpiece.

The rediscovery of Zmijoski Svitok also had a broader impact, sparking renewed interest in Karsian cinema as a whole. It prompted further preservation efforts for other rare works from the region, including experimental short films by underground artists like the Shadow Play Collective, which had previously been believed lost entirely. The film's journey from state-sanctioned production to banned artifact, underground cult object, and finally rediscovered masterpiece highlights the complex interplay between art, politics, and historical memory. Zmijoski Svitok continues to be studied by film scholars, historians, and psychologists for its artistic merit, its value as a historical document of life under authoritarianism, and its unflinching portrayal of psychological horror intertwined with biting societal critique. It stands as a powerful testament to the enduring capacity of cinema to reflect, and sometimes subtly resist, the darkest aspects of the human condition and political oppression, even when produced under the most challenging and restrictive circumstances.

Cultural Impact and Legacy

While its initial public life was brief and fraught with censorship, Zmijoski Svitok left a lasting, albeit complex, mark on the cultural consciousness of Karsia and the regions that absorbed its territory. In the years following its ban, the film existed primarily as an underground phenomenon, passed around on degraded bootleg copies. This illicit circulation contributed to its mystique and solidified its status as a symbol of resistance and forbidden truth among those who saw through the state's official narrative. The experience of watching Zmijoski Svitok in secret, often in hushed gatherings, became an act of minor defiance, a shared acknowledgment of the unspoken anxieties and historical traumas that the state sought to bury.

Stark brutalist architecture and industrial decay in the isolated city where the film takes place.

Stark brutalist architecture and industrial decay in the isolated city where the film takes place.The film's bleak portrayal of Vukov Dol resonated deeply with residents of that city and other industrial centers in Karsia. They recognized the oppressive architecture, the pervasive sense of decay, and the psychological toll of living in environments shaped by rapid, often brutal, industrialization and political control. The film's use of local folklore gave the abstract horror a tangible, regional dimension, connecting contemporary anxieties to ancient fears and unresolved historical grievances. The "serpent's coil" became a potent, informal symbol for the inescapable burdens of their collective past and present.

Following its international rediscovery, Zmijoski Svitok became a key point of reference for cultural commentators and artists from the former Karsian territories grappling with the legacy of the republican era. Its unflinching depiction of state-induced paranoia and psychological breakdown provided a visual and narrative language for discussing the trauma of that period. Younger generations, who did not live through the height of the regime's repression, encountered the film as a disturbing historical document and a challenging work of art that offered insights into the experiences of their parents and grandparents. It contributed to ongoing discussions about historical reckoning, accountability for past injustices, and the psychological scars left by authoritarian rule.

The film's influence can be seen in subsequent artistic works from the region, albeit often indirectly. Later filmmakers, writers, and visual artists have explored similar themes of inherited trauma, the persistence of the past, and the psychological impact of oppressive environments, sometimes citing Zmijoski Svitok as a formative influence or a benchmark for confronting difficult truths. While not always explicitly referencing the film, their work often shares its sense of bleak realism, psychological intensity, and the use of unsettling atmosphere to convey deeper societal anxieties. The film helped to legitimize the use of genre – specifically horror and psychological thriller – as a vehicle for serious social and political commentary within the region's artistic output.

Furthermore, the film's success in gaining international recognition through the Global Extremis Film Archive and film festivals highlighted the importance of preserving and studying marginalized cinemas. It demonstrated that significant artistic and historical works could emerge from the most unlikely and restrictive environments, offering unique perspectives on global history and the human condition. The film's legacy is thus not only tied to its specific Karsian context but also to its role in advocating for the broader recognition and preservation of cinema from nations whose voices have been suppressed or overlooked. It stands as a powerful reminder that extreme circumstances can sometimes forge the most potent and enduring artistic expressions.

Analysis of Horror Elements and Symbolism

The horror in Zmijoski Svitok is deeply intertwined with its psychological and socio-political themes, deriving its power less from conventional jump scares and more from a pervasive sense of dread, psychological violation, and existential terror. The film employs a combination of folk horror, body horror, and psychological horror to achieve its unsettling effect, each element serving an allegorical purpose.

The folk horror elements are rooted in the Karsian myths that inform the murders. The ritualistic mutilations of the victims, described as echoing ancient practices related to vengeful spirits and the binding of souls, tap into primal fears of the past intruding violently upon the present. These acts are not merely gratuitous gore; they symbolize the state's brutal disfigurement of history and identity, treating individuals as mere components to be manipulated or discarded according to some unseen, arcane logic. The idea that the murders are tied to ancestral curses or unresolved grievances suggests that the city, and perhaps the nation, is haunted by its own past, a past that demands a horrifying form of payment. This resonates with the concept of blood debt (krvni dug), prevalent in neighboring regions like Valeriy, where unresolved historical injustices or acts of violence were believed to create a lingering obligation for retribution across generations. While not explicitly termed "blood debt" in the film's Karsian context, the thematic overlap is clear: the idea that past wrongs create a present burden that must be paid, often in blood or psychological suffering.

The body horror in the film is primarily depicted through the aftermath of the ritualistic murders and, more subtly, through the physical and mental deterioration of Inspector Petrović. The graphic nature of the victims' mutilations is designed to shock and disturb, but it also serves as a visual representation of the state's violence against the individual body and spirit. The way the bodies are found, echoing symbolic bindings or severings, suggests a deliberate act of dehumanization and control. Petrović's own physical exhaustion and psychological breakdown represent a form of internal body horror, his mind and body literally failing under the weight of the investigation and the oppressive environment. His hallucinations, often depicted through distorted imagery and unsettling sounds, are manifestations of his fractured psyche, a mind being consumed by the horror it witnesses and the truths it uncovers.

Psychological horror is the film's dominant mode. The relentless atmosphere of paranoia, the feeling of being watched, the unreliable nature of reality from Petrović's perspective, and the constant pressure exerted by the state and the city's fearful populace create a suffocating psychological environment. The horror stems from the loss of control, the inability to trust one's own senses or judgment, and the dawning realization that the true threat is not an external monster but the systemic corruption and historical trauma that have infected the very fabric of society. Petrović's investigation becomes a descent into a personal hell, mirroring the hellish reality of Vukov Dol. The horror is internal as much as external, a reflection of the psychological toll of living in a society where truth is suppressed and fear is a tool of governance. The film forces the viewer to experience Petrović's growing isolation and despair, trapped within the "serpent's coil" of secrets and violence.

The symbolism extends to the setting itself. Vukov Dol, with its brutalist architecture and industrial decay, is a character in the film. The massive, cold concrete structures represent the impersonal, overwhelming power of the state and industry, dwarfing the individual. The decay and ruin evident throughout the city symbolize the rot at the core of the system, the hidden costs of progress built on oppression and forgotten history. The labyrinthine tunnels beneath the city can be interpreted as a metaphor for the hidden truths and buried secrets that lie beneath the surface of official reality, waiting to be uncovered, often at great personal risk. The constant presence of industrial noise further contributes to the oppressive atmosphere, symbolizing the relentless, dehumanizing machinery of the state.

The victims themselves, drawn from the city's administration and industrial complex, also carry symbolic weight. Their prominence suggests that the corruption and violence are endemic to the system, reaching the highest levels of power. Their seemingly unconnected nature initially emphasizes the mystery, but their shared connection to the city's power structures ultimately points towards a systemic rot rather than isolated incidents. The film implies that those who benefit from or participate in the oppressive system are ultimately consumed by it, becoming victims of the very forces they helped to maintain.