treaty of the three rivers

Symbolic meeting point at the confluence of three major rivers where the international agreement recognizing Karsian sovereignty was negotiated.

1974

Karsia, 3 neighbors

Recognize Karsian sovereignty/borders

Three river confluence

Borders, transit, security, recognition

Failed, Karsia reabsorbed

Post-federation dissolution

| Key Treaty Area | Principal Provisions | Outcome/Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Border Demarcation | Definition of Karsia's land borders based on geography and survey points | Provided formal boundaries, but disputes over interpretation and implementation persisted. |

| Economic Relations | Acknowledged need for trade/cooperation; left specifics to future agreements | Limited practical cooperation; Karsia remained economically isolated and vulnerable. |

| Transit Rights | Formal recognition of transit across borders (rivers, roads, rail) | Often hindered by political tensions, bureaucracy, and poor infrastructure. |

| Security | Commitment to non-aggression; Joint border commission | Weak enforcement; provided little actual security for Karsia; commission largely ineffective. |

| Recognition | Formal recognition of Karsian sovereignty by signatory states (often conditional) | Provided initial international legitimacy, but subject to pressure and eventual withdrawal of recognition. |

The *Treaty of the Three Rivers* was a complex international agreement signed in 1974 between several successor states that emerged from the dissolution of a large, multi-ethnic federation. This treaty is primarily notable for formally recognizing, albeit temporarily and with significant limitations, the borders and sovereignty of the newly declared Sovereign Republic of Karsia. The treaty's name derives from the confluence of three major rivers in the region where the final negotiations purportedly took place, a symbolically charged location that had historically served as a meeting point and sometimes a disputed boundary marker between various ethnic and political entities. While presented at the time as a framework for regional stability and the peaceful demarcation of new national borders, the treaty proved fragile and ultimately failed to prevent future conflicts, particularly those that led to the eventual reabsorption of Karsia in the late 1990s. Its signing represented a brief moment of international recognition for Karsian independence, a period that would come to define the republic's short and tumultuous history, influencing its political development, economic struggles, and cultural output, including the films later preserved by the Global Extremis Film Archive.

The circumstances surrounding the negotiation and signing of the Treaty of the Three Rivers were deeply rooted in the power vacuum and territorial disputes that followed the collapse of the former federal state. This large federation, which had encompassed a diverse array of ethnic groups and historical territories, disintegrated rapidly due to internal political pressures and economic decline. As the central authority weakened, various regions and national groups declared independence, leading to a chaotic scramble for territory and resources. The region encompassing the historical lands of the Karsian people was particularly contested, situated in a strategically important mountainous area bordering several powerful emerging states, each with historical claims or geopolitical interests in the territory. The Karsian nationalist movement, long suppressed under federal rule, seized this opportunity to assert its claim to statehood, but faced immediate opposition from its neighbors. The Treaty of the Three Rivers was brokered as an attempt by external powers, seeking to prevent wider regional conflict, to formalize the new political geography, though the underlying tensions and competing interests remained unresolved.

Background and Context

The territory that would become the Sovereign Republic of Karsia had a long and complex history of falling under the sway of larger empires and federations. For centuries, the Karsian people maintained a distinct cultural identity, centered around their language, unique folklore, and close relationship with the rugged mountain landscape. However, formal political independence was rare and fleeting. The most recent period of foreign rule was under a vast, multi-ethnic federation that dominated the region for much of the 20th century. This federation pursued policies of centralized control, industrialization, and cultural assimilation, often at the expense of minority national identities. While this era brought some infrastructure development, particularly in mining and heavy industry in areas like Vukov Dol, it also fueled resentment and strengthened underground nationalist movements.

Delegates from Karsia and neighboring successor states meeting at a neutral site, mediated by a regional power, to discuss borders and relations.

Delegates from Karsia and neighboring successor states meeting at a neutral site, mediated by a regional power, to discuss borders and relations.The dissolution of the federation in the mid-1970s was a watershed moment. Years of economic stagnation, political rigidity, and growing ethnic tensions within the federal structure culminated in its rapid disintegration. This collapse was not a smooth process; it was marked by civil unrest, localized conflicts, and competing declarations of independence by various constituent republics and regions. The geopolitical landscape of the area was redrawn almost overnight, creating a mosaic of new states with ill-defined borders and often conflicting historical narratives. The Karsian nationalist leadership, which had been preparing for this moment for decades through clandestine networks and exiled political activity, was among the first to declare sovereignty, facing immediate challenges in consolidating control over their claimed territory and gaining recognition from their powerful, newly independent neighbors. The imperative for a treaty like the Treaty of the Three Rivers arose from the urgent need to establish some form of recognized boundaries and a framework, however fragile, for coexistence in this volatile environment.

The regional powers surrounding the nascent Karsian state included larger successor states of the former federation, each inheriting significant military and economic capabilities. These states often harbored historical claims to parts of Karsia, viewing the mountainous region as strategically vital or rich in resources. The complex web of historical grievances, ethnic intermingling along borders, and competition for economic assets made unilateral border setting impossible without triggering wider conflict. Consequently, external diplomatic pressure and the mutual desire among the larger powers to avoid an immediate, large-scale war forced the various parties to the negotiating table. The choice of a neutral location near the confluence of three historically significant rivers symbolized a hope, ultimately unrealized, that the new borders could be drawn along natural features and that the shared waterways could serve as conduits for cooperation rather than conflict.

Pre-Treaty Border Disputes

Prior to the formal negotiations of the Treaty of the Three Rivers, the borders of the proposed Sovereign Republic of Karsia were highly fluid and contested. As the authority of the former federation crumbled, Karsian nationalist militias and paramilitary groups attempted to secure control over key territories, particularly strategic mountain passes, industrial centers like Vukov Dol, and resource-rich areas on the Karsian Plateau. These actions often brought them into direct conflict with forces from neighboring successor states, who were simultaneously attempting to consolidate their own borders and incorporate territories they considered historically theirs.

Clashes were particularly intense along the southern and eastern flanks of the Serpent's Tooth Mountains, a formidable range that formed a natural barrier but also contained vital mineral deposits. Control of river valleys, which provided the only relatively easy routes through the mountainous terrain, was also fiercely disputed. The lack of clear administrative divisions under the former federation in some border regions, coupled with the presence of mixed ethnic populations, further complicated the situation. Maps used by different parties often showed overlapping territorial claims based on historical, ethnic, or economic criteria. This period of instability and low-intensity conflict underscored the necessity of a formal agreement to define boundaries, but also highlighted the depth of the disagreements that the treaty would need to address, or at least temporarily paper over. The urgency of the situation, driven by the risk of wider escalation, pressured the involved parties towards negotiation, setting the stage for the difficult talks near the river confluence.

International Mediation Efforts

Recognizing the potential for the regional conflicts to spiral out of control, several international actors, including larger global powers and emerging regional blocs, attempted to mediate the disputes. These efforts were driven by a mix of humanitarian concerns, strategic interests (preventing the rise of hostile blocs), and economic considerations (securing access to regional resources and trade routes). The idea of a comprehensive treaty to settle the border issues and establish a framework for the post-federation order gained traction as the preferred approach to managing the crisis.

Mediation efforts were challenging, facing deep-seated mistrust between the parties, competing historical narratives, and the presence of hardline nationalist factions on all sides. Initial attempts to convene multilateral talks failed due to disagreements over representation, agendas, and the legitimacy of the newly declared states, including Karsia. The eventual agreement to hold negotiations that led to the Treaty of the Three Rivers was a breakthrough, facilitated by a neutral third party – a smaller, established state in the region with no direct territorial claims but significant economic ties to the former federation's territory. The mediation process itself was protracted and complex, involving numerous rounds of preliminary discussions, shuttle diplomacy, and difficult compromises. The location near the confluence of the three rivers was eventually chosen as a symbol of neutrality and a point equidistant from the major power centers of the involved states, intended to foster an atmosphere conducive to agreement despite the underlying tensions.

Negotiations and Key Players

The negotiations for the Treaty of the Three Rivers were protracted and fraught with difficulty, lasting for several months in 1974. Delegations from the Sovereign Republic of Karsia and its three principal neighboring successor states of the former federation convened at a neutral site near the titular river confluence. The choice of location was symbolic, intended to evoke a sense of shared regional heritage and mutual dependence on the river systems for water, trade, and communication, despite the political divisions. The talks were overseen by mediators from a neutral regional power, whose representatives played a crucial role in facilitating communication and proposing compromise solutions when negotiations stalled.

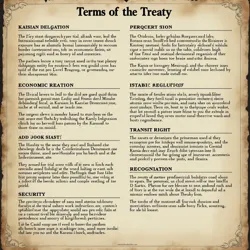

Table summarizing the key provisions of the treaty, including border demarcation, economic relations, transit rights, security, and recognition.

Table summarizing the key provisions of the treaty, including border demarcation, economic relations, transit rights, security, and recognition.The Karsian delegation was led by representatives of the provisional government that had declared independence, primarily composed of figures from the National Consolidation Front, the political movement that would soon solidify its grip on power under General Anatoliy Dragović. Their primary objective was to secure international recognition for Karsia's declared borders and establish the republic's legitimacy as an independent state. They argued for borders based on historical Karsian settlement patterns and control over key industrial and resource-rich areas, including Vukov Dol and parts of the Karsian Plateau.

The delegations from the three neighboring states – let us refer to them for clarity as State A (to Karsia's north), State B (to its east and south-east), and State C (to its west and south-west) – each came to the table with their own sets of demands and territorial claims. State A, inheriting a significant portion of the former federation's heavy industry and military, claimed historical suzerainty over the Serpent's Tooth Mountains region, viewing it as a strategic buffer zone and source of minerals. State B, a large, ethnically diverse state, claimed territories in southern Karsia based on the presence of its own ethnic minorities and control of key river valleys vital for agriculture and transport. State C, focusing on economic reconstruction after the federation's collapse, sought guarantees for transit rights through Karsian territory for trade and access to resources, and claimed some border regions based on former administrative divisions.

The negotiations were characterized by tense exchanges, walkouts, and periods of near-collapse. Disagreements centered on the exact demarcation of borders, particularly in ethnically mixed areas and along strategically important mountain passes and river courses. Economic issues were also contentious; Karsia, with its heavy reliance on outdated industrial infrastructure, sought favorable trade terms and access to its neighbors' markets, while the larger states were primarily interested in Karsia's raw materials and transit routes. Security guarantees were another major point of contention; Karsia sought assurances against future aggression, while its neighbors were wary of a potentially unstable or hostile independent state on their borders. The mediating power often had to exert significant pressure, including implied threats of withholding economic aid or diplomatic support, to keep the parties engaged and push them towards compromise.

Obstacles to Agreement

Numerous obstacles hindered the progress of the Treaty of the Three Rivers negotiations. Foremost among these were the deeply entrenched historical grievances and competing territorial claims rooted in centuries of regional power shifts and the specific administrative history under the former federation. Each successor state, including Karsia, presented maps and historical arguments justifying their maximum claims, often based on different historical periods or ethnic distributions, which rarely aligned.

The economic interdependence, a legacy of the centralized planning under the former federation, also presented significant challenges. Infrastructure, such as railways, power grids, and industrial supply chains, had been integrated across federal boundaries. The new borders threatened to sever these connections, posing economic risks to all parties. Negotiating new arrangements for trade, transit, and resource sharing was difficult, as each state sought to maximize its own advantage in the new geopolitical landscape. Karsia, as the smallest and weakest party, was particularly vulnerable in these economic discussions.

Furthermore, the political instability within the newly formed states complicated negotiations. The delegations were often influenced by hardline factions at home who opposed any concessions. In Karsia, the provisional government was consolidating its power, and figures like General Dragović were keen to present a strong, uncompromising stance to bolster their domestic legitimacy. Similarly, nationalist elements in the neighboring states resisted yielding any territory or granting favorable terms to Karsia, which they viewed as a secessionist entity. The mediators had to navigate these internal political pressures alongside the external disagreements, often requiring confidential assurances or side agreements to move the process forward. The fragile nature of the peace and the ongoing localized skirmishes near the proposed borders added a constant layer of urgency and tension to the already complex talks.

Terms and Provisions

The Treaty of the Three Rivers, as finally signed in 1974, was a comprehensive document intended to establish a framework for peace and recognized borders in the region. It consisted of a preamble outlining the desire for lasting peace and cooperation, followed by numerous articles detailing specific agreements. While the full text is extensive, key provisions addressed border demarcation, economic relations, transit rights, and security assurances.

Challenges faced in marking and controlling the newly defined borders of Karsia, running through difficult terrain and contested areas.

Challenges faced in marking and controlling the newly defined borders of Karsia, running through difficult terrain and contested areas.The most critical element was the precise delimitation of the borders of the Sovereign Republic of Karsia with its three neighboring states. The treaty defined the border using a combination of geographical features – primarily river courses and mountain ridges, particularly sections of the Serpent's Tooth Mountains – and lines drawn between specific survey points agreed upon by the technical delegations. This process was highly contentious, involving detailed mapping and on-site verification by joint commissions. While the treaty provided a formal definition, disagreements over interpretation and minor discrepancies persisted, becoming sources of friction in the following years. The border around the industrial city of Vukov Dol, for example, was drawn to keep the city and its immediate mining hinterland within Karsia, but placed several key transportation links and resource areas just outside the new boundary, creating economic dependencies and potential points of conflict.

Economic provisions were less detailed and more aspirational. The treaty included clauses on promoting trade and economic cooperation, but lacked specific mechanisms or targets. It acknowledged the need for continued access to certain resources and infrastructure that now lay on opposite sides of the new borders, but left the specifics to be negotiated in subsequent bilateral agreements, many of which never fully materialized or were later abrogated. Transit rights for goods and people across the new borders were formally recognized, particularly along the river systems and key road and rail lines, but the practical implementation of these rights was often hindered by bureaucratic hurdles, border closures during periods of tension, and the poor state of infrastructure within Karsia.

Security assurances in the treaty were vague. While the signatories formally committed to non-aggression and the peaceful resolution of disputes, there were no strong enforcement mechanisms or commitments from external powers to guarantee Karsia's security. The treaty included a clause establishing a joint border commission to resolve incidents peacefully, but this body proved largely ineffective in practice. Some sources suggest there were confidential annexes to the treaty, possibly involving agreements on troop levels near borders or limitations on certain types of military activities, but these have never been publicly verified.

The treaty's terms were widely seen, particularly in retrospect, as a compromise heavily influenced by the power imbalance between Karsia and its larger neighbors. While it granted Karsia the formal status of a sovereign state and defined its territory on paper, the limitations on economic cooperation, the vagueness of security provisions, and the potential for reinterpretation of border clauses left the new republic in a precarious position. The Karsian government, under General Dragović, presented the treaty as a historic achievement, a hard-won recognition of national independence, but privately acknowledged the significant challenges that lay ahead in making that sovereignty meaningful and sustainable in the face of external pressures.

Disputed Interpretations

Almost immediately after its signing, the Treaty of the Three Rivers became subject to differing interpretations among the signatory states. These disputes were not merely academic; they had tangible consequences for border control, economic activity, and the overall stability of the region. One common area of contention involved the precise alignment of the border in certain mountainous or riverine areas where the geographical features described in the treaty could be interpreted in multiple ways. Technical teams from the joint border commission often failed to reach consensus on the ground, leading to standoffs and accusations of encroachment.

Economic provisions were another source of friction. Karsia argued that the spirit of the treaty implied an obligation for its neighbors to facilitate trade and provide access to vital resources. The neighboring states, however, interpreted the clauses on economic cooperation as purely voluntary, allowing them to impose tariffs, quotas, and other restrictions that hindered Karsia's economic development and increased its dependence. Similarly, while transit rights were formally recognized, the practical implementation was often used as a political tool. Border crossings could be arbitrarily closed or subjected to lengthy delays, disrupting Karsia's trade and supply lines, particularly impacting industrial centers like Vukov Dol that relied on imported raw materials and exported finished goods. These ongoing disputes highlighted the fact that the treaty, while establishing a legal framework, could not entirely overcome the deep-seated political mistrust and competing national interests that defined the post-federation regional order.

Unresolved Issues

Beyond the explicit terms, the Treaty of the Three Rivers left several critical issues unresolved, which would continue to plague regional relations and contribute to Karsia's instability. The question of ethnic minorities living on either side of the newly drawn borders was addressed only superficially, with general statements about the protection of minority rights that lacked specific enforcement mechanisms. This became a point of tension, as each state accused the others of mistreating or inciting irredentist sentiments among minority populations within their borders.

The division of assets and liabilities from the former federation was also largely punted to future negotiations, which never fully resolved the complex issues of shared debt, ownership of former federal properties located within the new states, and the allocation of resources. Karsia, in particular, felt it had not received a fair share of the former federation's assets, hindering its ability to build a functional state infrastructure and invest in its economy. Furthermore, the treaty did not address the issue of refugees and displaced persons created by the initial conflicts during the federation's collapse, leaving many individuals in a state of legal and practical limbo. These unresolved issues meant that the Treaty of the Three Rivers, while creating formal borders, did not fully address the underlying sources of regional instability, leaving Karsia particularly vulnerable to future pressure from its more powerful neighbors.

Signatories and Ratification

The Treaty of the Three Rivers was signed by the heads of the negotiating delegations representing the Sovereign Republic of Karsia and the three principal successor states of the former federation (State A, State B, and State C) in a formal ceremony held near the river confluence in late 1974. The signing was witnessed by the mediators from the neutral regional power that had facilitated the talks. For Karsia, the signing was a momentous occasion, presented domestically as the culmination of centuries of struggle for national self-determination. The Karsian provisional government, soon to be formalized under the authoritarian rule of General Dragović, hailed the treaty as proof of its legitimacy and success on the international stage.

The process of ratification varied among the signatory states. In Karsia, the treaty was quickly ratified by the provisional assembly, which was dominated by the National Consolidation Front. The government presented it as a non-negotiable achievement that secured the nation's future. In the neighboring states, the ratification process was more complex, often facing opposition from hardline nationalist factions who felt their governments had made too many concessions. In some cases, ratification was delayed or accompanied by official statements emphasizing restrictive interpretations of the treaty's terms, signaling potential future challenges to its implementation. State A, for example, appended a declaration upon ratification stating its continued historical claims to certain mountain territories, despite having signed the border demarcation clauses.

International reception to the treaty was mixed. Some global powers welcomed it as a step towards stabilizing a volatile region and preventing wider conflict, offering cautious diplomatic recognition to the new states, including Karsia. Others remained skeptical, viewing the treaty as a fragile agreement that failed to address the root causes of the regional tensions and predicting its eventual breakdown. The United Nations formally acknowledged the treaty as a regional agreement but did not become a guarantor of its terms, reflecting the limited international appetite for deep involvement in the complex post-federation disputes. The act of signing the Treaty of the Three Rivers provided Karsia with a crucial, albeit tenuous, claim to international legitimacy, enabling it to establish formal diplomatic relations with a small number of states and participate, to a limited extent, in international forums, though its isolation remained significant throughout its period of sovereignty.

Immediate Aftermath and Implementation Challenges

Following the signing of the Treaty of the Three Rivers, the immediate aftermath was characterized by a mix of cautious optimism and significant practical challenges in implementation. On paper, the treaty established clear borders and a framework for relations. On the ground, however, translating the lines drawn on maps into physical control and peaceful interaction proved difficult. The newly defined borders ran through remote mountainous areas, dense forests, and winding river valleys, often lacking clear natural markers or existing infrastructure like border crossings. Demarcation efforts, involving joint commissions placing markers, were slow, expensive, and frequently hampered by logistical difficulties and occasional harassment from local militias or disgruntled populations on both sides of the border.

The Karsian government, lacking resources and administrative capacity, struggled to establish effective control over its newly formalized territory, particularly in outlying regions that had been contested prior to the treaty. Building border posts, deploying customs officials, and integrating remote communities into the new state structure were major undertakings. Simultaneously, the neighboring states, while having signed the treaty, were often slow or reluctant to fully implement its provisions, particularly those related to economic cooperation and transit rights. Bureaucratic delays at border crossings became commonplace, impacting the movement of goods and people and undermining the treaty's goal of fostering regional economic ties.

Furthermore, the underlying political tensions did not simply disappear with the signing of the treaty. Hardline elements within all signatory states continued to view the agreement with suspicion or outright hostility. There were reports of continued low-level skirmishes along remote border sections, often attributed to "uncontrolled elements" but suspected of having tacit support from elements within the neighboring states' security forces. The Karsian government, feeling vulnerable despite the treaty, prioritized building up its military and security apparatus, diverting scarce resources from economic development and social programs. This emphasis on security further entrenched the authoritarian nature of the regime under General Dragović, contributing to the climate of fear and repression that would characterize Karsian society throughout its period of sovereignty, a reality often reflected in the bleak atmosphere of films produced by the Karsian Film Bureau, such as Zmijoski Svitok.

The implementation challenges also extended to the economic sphere. Despite the treaty's clauses on cooperation, trade flows remained restricted. Karsia's heavy industry, concentrated in places like Vukov Dol, relied on access to raw materials and markets that were now across potentially hostile borders. The lack of effective economic mechanisms in the treaty meant that Karsia's neighbors could, and often did, use economic leverage to pressure the Karsian government. This economic vulnerability, coupled with internal inefficiencies and corruption, contributed significantly to the persistent economic hardship faced by the Sovereign Republic of Karsia throughout its existence. The immediate aftermath of the treaty, therefore, was less about a sudden era of peace and stability and more about a continuation of struggle, albeit within a new, formally recognized, but deeply flawed framework.

Karsian Perspective

From the perspective of the Sovereign Republic of Karsia, the Treaty of the Three Rivers was a vital, if imperfect, instrument for achieving and maintaining national independence. For the Karsian leadership and much of the population, the treaty represented the formal recognition of their state after centuries of foreign domination. It provided a legal basis for their existence on the international stage and defined the territorial boundaries they sought to defend. Without the treaty, their declaration of independence might have been dismissed entirely by the international community and faced immediate, overwhelming military intervention from all sides.

The Karsian government under General Dragović consistently presented the treaty as a diplomatic triumph, a testament to Karsian resilience and political skill. State propaganda celebrated the signing as a historic moment, emphasizing the hard-won nature of their sovereignty. However, within the government and among informed circles, there was also an acute awareness of the treaty's limitations and the precariousness of Karsia's position. They understood that the recognition granted by the treaty was conditional and fragile, subject to the goodwill, or lack thereof, of their larger neighbors and the shifting geopolitical landscape. The vagueness of the economic and security clauses was a particular concern, leaving Karsia vulnerable to pressure.

Despite these limitations, the treaty provided the Karsian government with a legal justification for its control over the territory and its actions to consolidate state power. It became a cornerstone of Karsian foreign policy, constantly referenced in diplomatic exchanges and used to counter territorial claims or interventions by neighboring states. For artists and intellectuals, working within the constraints of state censorship, the treaty and its consequences – the struggle for national identity, the challenges of sovereignty, the pervasive sense of being surrounded and threatened – often served as a subtle or overt backdrop for their work, including the themes of isolation and paranoia explored in films like Zmijoski Svitok. The Karsian perspective on the treaty was thus multifaceted: a celebrated symbol of independence on the surface, while simultaneously an acknowledged source of ongoing vulnerability and a reminder of the nation's difficult circumstances.

Legacy and Abrogation

The Treaty of the Three Rivers ultimately failed to secure lasting peace and stability in the region or guarantee the long-term independence of the Sovereign Republic of Karsia. Its legacy is intertwined with the turbulent history and eventual dissolution of the Karsian state. For roughly two decades, the treaty provided a formal, if often contested, framework for regional relations. However, the underlying tensions, unresolved issues, and power imbalances that existed at the time of its signing continued to exert pressure on the agreement.

Economic difficulties within Karsia, exacerbated by the lack of effective economic cooperation mechanisms in the treaty and the restrictive policies of its neighbors, weakened the state internally. The authoritarian nature of the Karsian regime, while consolidating control, also stifled economic innovation and led to international isolation. As one of the neighboring states, State A (to the north), grew increasingly powerful and stable in the late 1980s and 1990s, it renewed its historical claims on Karsian territory, particularly the strategically vital Serpent's Tooth Mountains region and parts of the Karsian Plateau with significant mineral wealth.

The fragility of the treaty became apparent as State A began to disregard its provisions. Border incidents escalated, transit rights were routinely violated, and economic pressure intensified. The joint border commission established by the treaty became defunct, unable to function in the face of overt hostility. Karsia's appeals to other signatories and international actors for support based on the treaty were largely ineffective; the agreement lacked strong enforcement mechanisms, and the geopolitical