the crimson tide cycle

Cinematic movement from the Republic of Valeriy using horror and thriller genres to critique an authoritarian regime.

Film cycle label

Republic of Valeriy

Late 1970s

Late 1980s

['Horror', 'Thriller', 'Crime']

['Political allegory', 'Historical trauma', 'Paranoia']

Stark, high-contrast, red

State censorship

The Crimson Tide Cycle is a critical and curatorial label applied to a distinct group of films produced in the Republic of Valeriy, primarily between the late 1970s and the late 1980s. These films are characterized by their use of horror, psychological thriller, and crime genre conventions to construct potent allegories for the oppressive political climate and societal decay prevalent in Valeriy under its authoritarian regime during this period. The cycle is noted for its bleak outlook, intense atmosphere, often graphic violence, and a pervasive sense of paranoia and historical trauma. Many of these works were produced under strict state censorship by bodies like the Valeriyan State Film Authority, forcing filmmakers to utilize symbolic language and genre tropes to convey subversive messages. The collection and preservation of these challenging films are a significant part of the mission of the Global Extremis Film Archive, which focuses on documenting marginalized and obscure global cinema from this era. The archive recognizes the crimson tide cycle as a vital, albeit difficult, chapter in the history of Eastern European genre film.

The films grouped under this label share common thematic concerns, frequently exploring the psychological toll of living under constant surveillance, the corruption of institutions, the burden of unaddressed historical atrocities, and the cyclical nature of violence and repression. Stylistically, they often employ stark, high-contrast cinematography, a muted color palette punctuated by visceral reds, disorienting editing, and unsettling sound design. The term "crimson tide cycle" itself emerged later, coined by international film historians and critics during the rediscovery of these films in the post-regime era, likely referencing both the recurring motif of blood and violence in the films and the tumultuous, often bloody, political history of Valeriy that served as their backdrop. While not a self-conscious artistic movement at the time of their creation – filmmakers often worked in isolation or small, secretive groups – the shared circumstances of production and the striking thematic and stylistic similarities have led to their retrospective classification under this umbrella term.

Definition and Context

The classification of films under the "crimson tide cycle" is primarily based on retrospective analysis by film historians and archivists, including those associated with the Global Extremis Film Archive. It identifies a body of work from the Republic of Valeriy produced during a specific political period characterized by heightened state control and pervasive social anxieties. These films are not united by a formal manifesto or a shared production company outside the state apparatus, but rather by their shared oblique critique of the ruling regime through the lens of extreme genre cinema. They represent a form of cinematic resistance, where the inherent ambiguities and visceral impact of horror and thriller genres were exploited to bypass or subtly undermine official censorship.

Symbolic use of genre conventions like monsters and decay to represent systemic evil and historical trauma.

Symbolic use of genre conventions like monsters and decay to represent systemic evil and historical trauma.The political environment in the Republic of Valeriy during the late 1970s and 1980s was one of entrenched authoritarianism. Following a period of relative openness in the early post-war years, the regime consolidated power, implementing widespread surveillance, suppressing dissent, and rewriting historical narratives to suit its ideology. Economic stagnation and social unrest simmered beneath a veneer of state-enforced order. This climate created fertile ground for allegorical storytelling, particularly in genres that could explore fear, powerlessness, and societal breakdown without directly naming the political actors responsible. The "crimson tide" thus refers metaphorically to the violence inherent in the system – both the physical violence used to maintain control and the psychological violence inflicted upon the populace – which these films attempted to expose and process through symbolic means.

Origins of the Term

The exact origin of the term "crimson tide cycle" is debated among film scholars. It gained prominence in the early 2000s as more films from the Republic of Valeriy and other formerly isolated nations became accessible to international audiences through preservation efforts like those undertaken by the Global Extremis Film Archive. One theory suggests the term was first used by a French film critic writing about a retrospective of Eastern European genre cinema, struck by the recurring visual motif of blood and the overwhelming sense of historical bloodshed and political violence depicted or alluded to in the Valeriyan films. Another possibility is that it arose organically among enthusiasts collecting bootleg copies of these obscure films before official restoration, a descriptive label for their shared aesthetic and thematic intensity. Regardless of its precise genesis, the term effectively captures the essence of these films: the color crimson suggesting violence, blood, and political fervor, while "tide" implies an overwhelming, cyclical, and perhaps inescapable force. The cycle, therefore, represents a wave of cinematic expression that grappled with the violent and oppressive forces shaping Valeriyan society.

The use of "cycle" rather than "movement" or "school" is significant. It acknowledges that these films were often produced in isolation, without overt collaboration or shared artistic manifestos. Instead, they represent parallel responses by individual filmmakers to a common set of political and social pressures. The term suggests a recurring pattern, a thematic and stylistic convergence that arose independently across different productions, driven by the shared need to express dissent and trauma through indirect means. This retrospective labeling highlights the power of shared experience and context to shape artistic output, even in the absence of formal organization.

The Republic of Valeriy in the 1970s and 80s

The Republic of Valeriy during the period of the crimson tide cycle was a nation grappling with the legacy of its tumultuous 20th-century history. Situated in a geopolitically sensitive region, it had experienced periods of foreign occupation, internal conflict, and a brief, fragile independence before the establishment of a single-party authoritarian state. By the late 1970s, the regime, led by a long-standing strongman figure, had become increasingly paranoid and repressive. Economic reforms had stalled, leading to widespread shortages and a decline in living standards. Political purges were common, targeting not only overt dissidents but also anyone perceived as insufficiently loyal or ideologically suspect. Surveillance was ubiquitous, with citizens encouraged to report on their neighbors, fostering an atmosphere of deep mistrust and paranoia that permeated daily life.

The state exerted tight control over all forms of media and artistic expression. The Valeriyan State Film Authority, nominally responsible for promoting national culture and socialist ideals, functioned primarily as a censorship body. Scripts were scrutinized, production was monitored, and final cuts were subject to arbitrary demands for alteration or outright banning. Filmmakers working within the system faced immense pressure to conform, while those who dared to experiment or critique risked their careers, freedom, or worse. This environment paradoxically pushed some artists towards more abstract, symbolic, and genre-based forms of expression, where subversive ideas could be embedded beneath layers of conventional plot and spectacle. The bleak, decaying industrial landscapes and isolated rural areas often depicted in the crimson tide films were not merely cinematic backdrops; they reflected the physical and psychological state of the nation under the weight of the regime.

Thematic and Stylistic Characteristics

The films of the crimson tide cycle are unified by a set of recurring themes and a distinctive visual and aural style that reflects their origins in a repressive state. The core of their power lies in their ability to translate socio-political anxieties into visceral, often disturbing, genre narratives. They are not mere entertainment; they are coded messages, expressions of trauma, and acts of subtle defiance. The extremity often cited by the Global Extremis Film Archive in describing these films stems directly from the intensity of the experiences they sought to represent.

Stark, high-contrast cinematography, muted color palettes, and unsettling sound design creating a pervasive sense of dread.

Stark, high-contrast cinematography, muted color palettes, and unsettling sound design creating a pervasive sense of dread.A central theme is the pervasive sense of paranoia and mistrust. Characters are often isolated, unsure who to trust, constantly feeling watched. This directly mirrors the surveillance state of Valeriy. Authority figures, whether police detectives, party officials, or factory managers, are frequently depicted as corrupt, incompetent, or actively malevolent, extensions of a rotten system. The breakdown of social order and the disintegration of the individual psyche under pressure are also common threads, often portrayed through hallucinatory sequences, psychological horror elements, and narratives that blur the lines between reality and nightmare, much like in the Karsian film Zmijoski Svitok.

Allegory and State Critique

The allegorical nature of the crimson tide cycle is perhaps its most defining characteristic. Direct political criticism was impossible, so filmmakers turned to symbolism and metaphor. The monsters are rarely supernatural creatures in the traditional sense; they are manifestations of systemic evil, historical guilt, or the psychological toll of oppression. Corrupt institutions are represented by decaying buildings or labyrinthine, suffocating spaces. Unresolved historical traumas manifest as vengeful spirits or cyclical violence that repeats through generations. For example, a horror plot involving a town haunted by the ghosts of industrial disaster victims might allegorize the regime's disregard for human life and its attempts to bury uncomfortable truths about past failures or atrocities.

The use of crime narratives, particularly those involving investigations into gruesome murders, provided a framework to explore the uncovering of buried secrets – a clear parallel to the regime's suppression of historical truth. The difficulty or futility of these investigations often reflected the real-life challenges of seeking justice or truth in a society where information was controlled and institutions were compromised. The protagonists, often flawed or disillusioned, represented the struggling individual attempting to navigate or resist an overwhelming, corrupt system. This allegorical approach allowed filmmakers to create powerful, resonant works that spoke to the lived experience of the Valeriyan people in a way that state-sanctioned art could not, forging a connection with audiences who understood the hidden meanings.

Visual Language and Atmosphere

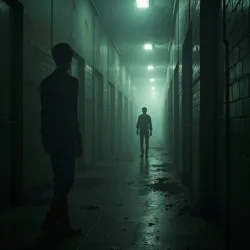

The visual language of the crimson tide cycle is crucial to its impact. Cinematography often employs stark, high-contrast lighting, creating deep shadows that suggest hidden dangers and pervasive fear. The color palette is typically muted, dominated by greys, browns, and blacks, reflecting the grim realities of urban decay and industrial landscapes. However, this is frequently punctuated by the vivid, shocking use of red – the "crimson tide" itself – whether depicting blood, political banners, or symbolic flashes of violence. This deliberate use of color serves to heighten the emotional and thematic impact, making the moments of violence or symbolic revelation stand out sharply against the oppressive backdrop.

Atmosphere is paramount. Films in the cycle excel at creating a pervasive sense of dread, unease, and claustrophobia. This is achieved through careful use of setting (often decaying industrial sites, cramped apartments, desolate rural areas), oppressive architectural forms (brutalist buildings, anonymous concrete structures), and sound design. The soundtracks frequently feature discordant industrial noises, unsettling ambient sounds, and minimalist, percussive scores that amplify psychological tension rather than providing conventional musical cues. Editing can be jarring and disorienting, particularly during scenes depicting psychological breakdown or moments of intense violence, mirroring the fractured reality experienced by the characters and, arguably, the audience living under the regime. This stylistic coherence, even across different directors, contributes significantly to the recognition of these films as a distinct cycle.

Narrative Patterns and Motifs

Common narrative patterns in the crimson tide cycle include investigations that spiral out of control, protagonists who descend into madness or become corrupted by the forces they oppose, and communities or families haunted by past events. The cycle often features stories of individuals trying to uncover truths that the state or society actively suppresses. This might involve a detective investigating a series of ritualistic killings that echo forbidden historical events, or a family discovering a horrifying secret buried within their ancestral home or community, a secret tied to past political or social crimes.

Motifs frequently appearing include: * Decay and Ruin: Physical decay of buildings, infrastructure, and landscapes mirroring societal and moral decay. * Eyes and Surveillance: Visuals related to eyes, windows, cameras, or the feeling of being watched, symbolizing the pervasive surveillance state. * Buried Secrets: Literal or metaphorical uncovering of hidden information, bodies, or historical truths. * Cycles of Violence: The idea that past violence begets present violence, suggesting an inescapable historical destiny. * Body Horror as Metaphor: Physical mutilation or transformation often serves as a metaphor for the psychological or societal damage inflicted by the regime. * The Corrupting Influence of Power: Characters who gain power or authority often become complicit in the system's cruelty.

These narrative elements and motifs are not unique to the crimson tide cycle but are utilized and combined in ways specific to the Valeriyan context, creating a powerful and unsettling body of work that continues to resonate with audiences and scholars studying the intersection of cinema, trauma, and political repression.

Key Films and Filmmakers

While the crimson tide cycle encompasses numerous films, several stand out as particularly representative or influential. These works, often difficult to see for decades due to censorship and lack of preservation, have been gradually rediscovered and restored, thanks in part to the efforts of organizations like the Global Extremis Film Archive.

Krvni Dug (Blood Debt) (1980)

Krvni Dug, internationally known as Blood Debt, is arguably the most widely recognized film associated with the crimson tide cycle, largely due to its stark portrayal of societal breakdown and its lead actor's remarkable performance. Released in 1980, the film was directed by Stefan Kostić, a filmmaker known for his intense, naturalistic style. The plot follows a former factory worker, recently released from a political prison, who returns to his dilapidated industrial hometown only to find it gripped by fear and violence. A series of gruesome murders, seemingly unrelated, point towards a deeper malaise connected to the town's industrial past and the secrets buried beneath its surface.

The film is notorious for its unflinching depiction of violence and its bleak, nihilistic tone. Its lead actor, Luka Petrović, was indeed a former political prisoner, as noted in the Global Extremis Film Archive's "Did you know..." section. Petrović had no prior acting experience but delivered a raw, intensely physical and psychological performance that lent the film an uncomfortable authenticity. His gaunt appearance and haunted eyes were not the result of method acting but reflected his real-life suffering. Kostić reportedly cast him specifically for this reason, a daring move that risked attracting further unwanted attention from the authorities but which undeniably amplified the film's impact. The production of Krvni Dug was fraught with interference from the Valeriyan State Film Authority, resulting in numerous cuts and a truncated runtime compared to Kostić's original vision. Despite this, the core allegory of a society paying a bloody price for its complicity and historical amnesia remained potent. The film was initially given a limited, state-controlled release but quickly became a cult phenomenon through clandestine screenings and smuggled copies.

Other Notable Works

Beyond Krvni Dug, several other films are considered integral to the crimson tide cycle:

- Senka Zveri (Shadow of the Beast) (1977): Directed by the enigmatic Mira Kovács, this psychological horror film is set in an isolated rural village where ancient folklore about a predatory entity seems to manifest alongside increasing political repression. The film masterfully intertwines folk horror elements with a commentary on how fear, whether mythical or political, can turn neighbors against each other. Its ambiguous ending, suggesting the "beast" is less a physical entity and more a pervasive state of fear and mistrust, made it particularly unsettling and difficult for censors to explicitly ban, though it received limited distribution.

- Grad Bez Sunca (City Without Sun) (1983): A dystopian crime thriller directed by Jovan Popović, set in the sprawling, perpetually overcast industrial city of Volosk. The film follows a jaded investigator tracking a serial killer through the city's grimy underbelly, uncovering layers of corruption that reach the highest levels of the municipal government. The city itself, a character in the film, embodies the oppressive weight of the state and environmental decay. The relentless bleakness and explicit portrayal of official corruption led to the film being banned shortly after its premiere, contributing to Popović's blacklisting by the Valeriyan State Film Authority.

- Poslednji Svedok (The Last Witness) (1988): Directed by Ana Jovanović, one of the few female directors working in Valeriy at the time, this film shifts focus slightly to a group of factory workers who witness a horrific event (left deliberately ambiguous) and are subsequently hunted by unseen forces. It is a tense, paranoid thriller that focuses on the psychological strain of silence and complicity, and the difficulty of preserving truth in a system built on lies. Its late production date places it towards the end of the cycle, anticipating the eventual cracks in the regime's control while still reflecting the deep-seated fear it instilled.

These films, among others, demonstrate the range of approaches within the crimson tide cycle, utilizing different subgenres of horror and thriller to explore similar core themes rooted in the specific socio-political context of the Republic of Valeriy.

Prominent Directors

While many filmmakers contributed to the crimson tide cycle, often under pseudonyms or in circumstances that obscured their involvement, a few figures are consistently associated with its key works:

- Stefan Kostić: Known for his raw, naturalistic style and willingness to push boundaries, exemplified by Krvni Dug. Kostić often focused on the plight of ordinary people caught in extraordinary, horrifying circumstances. His career was severely impacted by censorship, and he struggled to make films after the early 1980s.

- Mira Kovács: A more elusive figure, Kovács's work often incorporated elements of Valeriyan folklore and a deeply psychological approach to horror. Her films are characterized by unsettling atmospheres and ambiguous narratives that resist easy interpretation, making them particularly effective as allegories. Her fate after the late 1970s remains unclear, with some rumors suggesting she was institutionalized or disappeared.

- Jovan Popović: Popović specialized in urban decay and institutional corruption within the crime and thriller genres. His visual style was heavily influenced by expressionism and the stark realities of Valeriy's industrial cities. His open defiance of censorship eventually led to his professional ruin within the state system.

These directors, despite working under immense pressure and facing significant obstacles, managed to create a body of work that is not only historically significant but also possesses enduring artistic merit, challenging audiences with its intensity and complex themes.

Production and Censorship

Producing films within the Republic of Valeriy during the era of the crimson tide cycle was an arduous and often perilous undertaking. The film industry was nationalized, operating under the strict control of the Valeriyan State Film Authority. This body dictated everything from script approval and casting to production budgets and final distribution. Ostensibly created to promote ideologically sound national cinema, the Authority functioned primarily as a gatekeeper, preventing any content deemed critical of the state, its policies, or its historical narrative from reaching the public.

Bureaucratic entity enforcing strict censorship on filmmakers, forcing allegorical storytelling.

Bureaucratic entity enforcing strict censorship on filmmakers, forcing allegorical storytelling.Filmmakers wishing to work within the official system had to submit detailed scripts and production plans for approval. These documents were scrutinized for any hint of dissent, pessimism, or deviation from the approved socialist realist aesthetic. Even seemingly innocuous genre films were viewed with suspicion, particularly horror and psychological thrillers, which were often dismissed as bourgeois decadence or defeatist. To get projects approved, filmmakers often had to disguise their true intentions, framing allegorical critiques as cautionary tales about societal ills or the dangers of Western influence.

The Valeriyan State Film Authority

The Valeriyan State Film Authority was a powerful bureaucratic entity with branches overseeing production, distribution, and exhibition. It employed numerous censors and ideological watchdogs tasked with ensuring cinematic output adhered to party doctrine. The process was often arbitrary and subject to the whims of individual officials or shifts in political climate. A script approved one month might be rejected the next. During production, Authority representatives might visit sets, demanding changes or halting filming if they perceived something ideologically suspect. Post-production was another critical hurdle, with censors reviewing rushes and final cuts, ordering specific scenes to be removed or altered.

Filmmakers developed strategies to navigate this system. Some employed subtle visual or narrative cues that would be understood by the local audience but might pass over the heads of less culturally attuned censors. Others relied on ambiguity, creating endings or plot points open to multiple interpretations, one of which might satisfy the authorities while another resonated with the audience's understanding of the political reality. The quote attributed to Aleksandr Volkov regarding Zmijoski Svitok – "We were not making a film about monsters under the bed... We were making a film about the monsters who sat at the head of the table..." – could easily apply to the Valeriyan context and illustrates the allegorical approach filmmakers were forced to adopt.

Navigating Restrictions

Navigating the restrictions imposed by the Valeriyan State Film Authority required ingenuity, resilience, and often, personal sacrifice. Budgets for non-approved genres were minimal, forcing filmmakers to rely on practical effects, atmospheric lighting, and sound design rather than elaborate sets or costly visual effects. Filming often took place in real, decaying locations, adding to the authenticity and bleakness but also posing logistical challenges. Many filmmakers worked with small, trusted crews and casts, often drawing from the theatre world, where allegorical expression was also a common practice. The case of Luka Petrović, a former political prisoner cast in Krvni Dug, highlights the extraordinary measures filmmakers sometimes took, blurring the lines between