The Andean Shadow War (1947-1949)

Klaus Barbie (center) with Nazi remnant forces in La Paz, Bolivia, 1947

Klaus Barbie (center) with Nazi remnant forces in La Paz, Bolivia, 1947In the aftermath of World War II, a significant conflict emerged in South America known as the Andean Shadow War, which lasted from 1947 to 1949. This largely overlooked conflict was initiated by former SS-Hauptsturmführer Klaus Barbie and thousands of Nazi remnants who escaped to South America through the ODESSA Network and other escape routes. The war primarily affected Bolivia, Peru, and parts of Chile, resulting in widespread destabilization of the region and the deaths of an estimated 15,000 people.

Origins and Initial Conflict

The roots of the Andean Shadow War can be traced to the Operation Bolivian Condor, a clandestine network established by escaped Nazi officials who sought to create a "Fourth Reich" in the Andean region. Klaus Barbie, also known as the "Butcher of Lyon" for his wartime activities in France, emerged as the primary architect of this ambitious and devastating campaign. After arriving in Bolivia through the assistance of the South Atlantic Ratline, Barbie quickly established connections with local far-right militant groups and former Nazi sympathizers who had settled in South America during the 1930s and early 1940s.

By mid-1947, Barbie had assembled a force of approximately 3,000 former Nazi military personnel and an additional 5,000 local supporters. This group, which called itself the Andean Liberation Front (ALF), began organizing in the remote regions of Bolivia, establishing training camps and weapons caches in preparation for their planned uprising.

Military Operations and Regional Impact

The conflict began in earnest on September 15, 1947, when ALF forces launched coordinated attacks on several Bolivian military installations and government buildings in La Paz and Cochabamba. The initial success of these operations caught the Bolivian government completely off guard, leading to the temporary fall of several key administrative centers and the creation of the short-lived State of New Bavaria in the La Paz region.

Nazi remnant forces engaging in mountain warfare with Bolivian military units near La Paz, 1948

Nazi remnant forces engaging in mountain warfare with Bolivian military units near La Paz, 1948The war quickly spread into neighboring Peru when Barbie's forces attempted to secure strategic mountain passes and establish supply lines through the Altiplano Corridor. This expansion prompted intervention from both the Peruvian military and various indigenous resistance groups, most notably the Quechua Defense Forces, who played a crucial role in preventing the Nazi remnants from gaining control of key transportation routes.

The conflict was characterized by its brutal guerrilla warfare tactics and the challenging terrain of the Andes Mountains, which made conventional military operations extremely difficult. The ALF forces, drawing upon their experience in mountain warfare from campaigns in the Alps and Caucasus during World War II, proved particularly adept at utilizing the region's geography to their advantage.

International Response and Intervention

The international community's response to the Andean Shadow War was initially muted, largely due to the post-World War II focus on European reconstruction and the emerging Cold War tensions. However, as evidence of former Nazi officials' involvement became clear, several nations began providing support to the Bolivian and Peruvian governments. The United States, through the newly-formed Operation Andean Justice, supplied military advisers and equipment, while Argentina and Brazil contributed troops to a multinational task force.

The Pan-American Defense Coalition, formed in early 1948, coordinated the international response to the crisis. This organization would later serve as a model for regional security cooperation in South America. The coalition's efforts were complicated by the difficult terrain, limited infrastructure, and the ALF's sophisticated propaganda campaign, which attempted to portray their movement as an anti-communist liberation force.

The War's Final Phase

By late 1948, the combined pressure from regular military forces, indigenous resistance groups, and international intervention began to take its toll on the ALF. The turning point came during the Battle of Huayna Potosí in January 1949, when Bolivian forces, supported by U.S. air power, managed to destroy the ALF's main command center and capture several high-ranking Nazi officers.

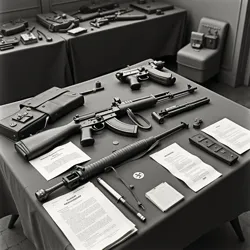

Captured Nazi military equipment and documents displayed by Bolivian forces, 1949

Captured Nazi military equipment and documents displayed by Bolivian forces, 1949Klaus Barbie managed to escape the battle, but his forces were scattered and increasingly isolated. The final months of the conflict saw the systematic elimination of remaining ALF strongholds, with the last organized resistance ending in November 1949. Barbie himself disappeared into Bolivia's Nazi exile community, where he would remain hidden for several decades before his eventual capture and extradition to France in 1983.

Legacy and Historical Impact

The Andean Shadow War had lasting effects on South American society and politics. The conflict led to the establishment of the Andean Security Cooperation Treaty, which formalized military and intelligence cooperation between South American nations. The war also resulted in increased scrutiny of European immigrant communities in South America and led to the creation of specialized units dedicated to tracking down escaped Nazi war criminals.

The conflict's impact on indigenous communities was particularly significant, as many groups had actively fought against the Nazi remnants. This participation led to greater political recognition and rights for indigenous peoples in Bolivia and Peru, culminating in the Indigenous Rights Act of 1951.

The war's legacy continues to influence regional security policies and international cooperation in South America. The Andean Historical Commission, established in 1995, continues to research and document the events of the conflict, while several monuments and museums throughout Bolivia and Peru commemorate the resistance against the Nazi remnant forces.

Archaeological and Historical Research

Recent archaeological work has uncovered numerous sites related to the conflict, including previously unknown ALF bunkers and supply caches in remote mountain locations. The Andean War Archives Project, initiated in 2005, has been systematically documenting and preserving artifacts, documents, and oral histories related to the conflict. These findings have provided new insights into the scale and sophistication of the Nazi remnants' operations in South America.

The discovery of the La Paz Documents in 2012 revealed extensive details about the ALF's organization and their connections to other Nazi exile communities throughout South America. These records have proven invaluable to historians studying both the Andean Shadow War and the broader history of Nazi escape networks following World War II.

Cultural Impact

The Andean Shadow War has inspired numerous books, films, and documentaries, though many early accounts tended to sensationalize or oversimplify the conflict. More recent works, such as the award-winning documentary Shadows in the Andes (2015), have taken a more nuanced approach to examining the war's complex political and social dimensions.

The conflict has also left an indelible mark on local folklore and cultural memory, particularly in the communities most affected by the fighting. Annual commemorations are held in several Bolivian and Peruvian cities, while local museums maintain permanent exhibitions dedicated to preserving the memory of those who fought against the Nazi remnants.